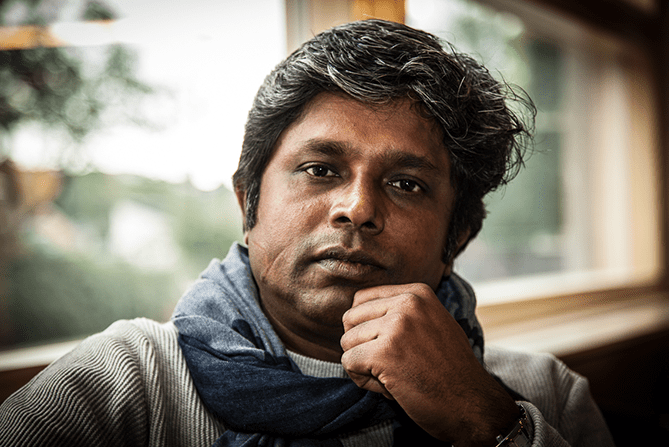

Bangladeshi publisher Tutul – with whom Margaret Atwood shared her 2016 PEN Pinter Prize – discusses exile, free thinking, and thirty years of the magazine and publisher Shuddhashar.

PEN Transmissions is English PEN’s magazine for international and translated voices. PEN’s members are the backbone of our work, helping us to support international literature, campaign for writers at risk, and advocate for the freedom to write and read. If you are able, please consider becoming an English PEN member and joining our community of over 1,000 readers and writers. Join now.

Tutul – Shuddhashar, the magazine, has existed for 30 years now. Of course, so much has changed in Bangladesh – and the wider world – in that time. What has been the most profound change in those three decades, for you?

Change is the rule of the world. We are all always living through constant change. In the past three decades, we have witnessed many significant political, cultural, and scientific shifts – the end of the Cold War, monopoly aggression, organised terrorism, the rise of religious nationalism and militancy, increase in authoritarian rule, a rise of xenophobia and intensified racism, the rapid spread of globalisation, and the dominance of internet-based communication. All these are significant, for me. The recent coronavirus pandemic, of course, has brought additional changes, the real global, local, and personal effects of which we are yet to understand.

Shuddhashar has many lives – as a writers’ group, a magazine, a press. We often think of writers’ groups as closed, perhaps exclusionary spaces, but Shuddhashar has always struck me as a space of openness. How important has the sense of community it has afforded been to those involved?

As a moderator, I can confidently say that Shuddhashar is indeed a very open platform. Many of those who started writing blogs in Bangladesh bridged the gap between the blogging world and the mainstream by publishing their first books with Shuddhashar. We published several activist bloggers during the early days.

Shuddhashar’s writers are free thinkers, but can be distinguished from those who simply wrote critically about religion. Many LGBTQIA+ writers, for instance, were with a part of Shuddhashar. As well as bloggers, we also published nonfiction, fiction, and poetry, and these forms had their own distinct communities – but there was never any dispute among the groups. At first, perhaps, mainstream writers didn’t like bloggers very much. That was during our magazine and book publishing time. But our door was never closed.

After the series of fatal assaults on publishers and writers in Dhaka in 2015, including an attack which you survived, you moved to Norway, to the Skien City of Refuge, where you have been based since 2016. You’ve been characterised as a ‘publisher in exile’; how does that exile affect how, what, and why you publish?

This is a very interesting question. I ask myself this almost every day. But, so far, I have been unable to find a satisfactory answer. I published a special magazine issue about exile for Shuddhashar this November, with exactly this question in mind.

People have to lose something during any kind of migration. And there’s a lot of shock and trauma that comes with an unprepared migration. You know, I was a successful book publisher in Bangladesh: I published more than a hundred books a year, and was also involved in editing and publishing Little Magazines. But suddenly I had to move away from that familiar life. Surviving by luck is a great joy. But I have to emphasise that just surviving is not a human life. For that reason, I was looking for ways to stay connected to my work – it was absolutely essential that I kept working, kept building on my skills, and kept trying to maintain good working connections with those left behind in Bangladesh. That’s how I started working on Shuddhashar online again.

It wasn’t easy. I didn’t receive the support I expected, and many people along the way discouraged me. But the stubbornness worked inside me anyway. My experiences helped me to start anew. In 2016, I was sick, injured, and traumatised; I had great difficulty imagining a path forward. But English PEN, PEN America, IPA, and in 2018 Norsk PEN, all encouraged me to continue my work by awarding me.

Since the early days of Shuddhashar as a publishing house, internationalism (and bringing the work of international writers to readers through translation) has been central to the press. With an international chilling of free expression, do you see Shuddhashar having a role in other national and linguistic contexts?

Yes – Shuddhashar was engaged in lots of translation work. We published the poetry of Hafeez (translated by Syed Shamsul Haq), Pablo Neruda (by Kajal Bandopadhyay), Tomas Transtromer (by Jewel Mazhar), Faiz Ahmed Faiz (by Mahmud Alam), the Marx-Yosar Dialogues (indebted to Rafiq um Munir Chowdhury), Marx in Soho (by Palash Ranjan Sanyal), The Apple of Samia Mukhamalbaf (by Aditi Falguni), Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (by Mustaq Sharif), Arundhati Roy’s The Broken Republic (by Luna Rushdie), interviews by Roy (by Hasan Morshed), and Novum Organum (by Fazlul Karim).

We have a plan to do more translation. Right now, we are working between English and Bangla and Norsk. We have a plan to publish some print books and ebooks, which I hope will included translated titles. We want more interaction with different thinking, as well as with different style.

What worries you most?

The culture of political and state bureaucracy in Bangladesh worries me the most. I fear opportunism, corruption, complacency, the use of people’s poverty and illiteracy as political tools. I think many publishers will come forward again to publish thought-provoking, critical, and controversial books if the normal life and safety of people can be ensured.

What gives you hope?

My passion, commitment, and dreams. I’m sure many more do the same. These same people are inspiring many more. I am sure there are many people in this world who want to open people’s eyes and sense, want to make people more open minded. One day these people will surely be able to make a big positive change.

Without subscribing too much to the idea of ‘duty’, how essential are the writer (and the reader) – and what they do – in our current moment?

A writers’ duty and responsibility is only in writing. But states and society must be able to give them a safe, fearless environment. If writers can write without the fear of censorship, blasphemy, and authoritarian madness, then they can influence people for the sake of humanity, democracy, and openmindedness.

In terms of readership, the state has many responsibilities. It must strongly commit to and make policy for promoting and encouraging reading. This much be a continuous programme. They have to understand it’s not less important than other aspects of infrastructural development. Because reading books is essential to human development – it is incomparable. The spine of any strong and truly effective democratic society is a strong reading culture.

Ahmedur Rashid Chowdhury is the publisher and editor of free speech website (magazine and book publisher) Shuddhashar. He survived an assassination attempt against him by Islamist extremists and currently lives in exile. He is the winner of the Shahid Munir Chowdhury best publisher Award 2013, PEN Pinter International Writer of Courage Award 2016, The Jeri Laber international freedom to publish Award 2016, International Publishers Association (IPA), Freedom to Publish Prize Finalist, 2016, International Publishers Association (IPA), Prix Voltaire Short List 2018 and Ossietzky Prize 2018.

Interview by Will Forrester, Editor.

Photo credit: Arne Olav Hageberg