Vaddey Ratner on memory, narrative history, and storytelling as a means of survival.

PEN Transmissions is English PEN’s magazine for international and translated voices. PEN’s members are the backbone of our work, helping us to support international literature, campaign for writers at risk, and advocate for the freedom to write and read. If you are able, please consider becoming an English PEN member and joining our community of over 1,000 readers and writers. Join now.

Vaddey – thanks so much for speaking with me. To begin, your novels In the Shadow of the Banyan and Music of the Ghosts both contend with a tension between holding memory and moving forwards after a violent disruption like the Cambodian genocide. How do you think about the act of transforming history into something that lives in the space of fiction?

I don’t approach my writing as an effort to transcribe history. I set out to honour the lives lost amid war and revolution, and to speak to the lives transformed in the aftermath. My first concern is that the novel, a work of fiction, must be utterly believable. It is a contained world, finite and intimate, populated by characters who must live and breathe on the page. I want you to care about that world and the people who inhabit it.

That’s describing it with a writerly eye, looking back. But when I sat down to write In the Shadow of the Banyan, it was the loss and pain I endured as a child that came to the forefront. The challenge was to render the experience as faithfully as I remembered it. At some point, as a writer, you forget that you’re describing suffering. You feel it. You relive it.

Your writing carries the weight of personal and collective memory, yet it also participates in shaping a public memorial to Cambodia’s history. As memory is not always linear – it circles, refracts, distorts – how do you navigate the complexity of remembering as an intimate act and memorialising as a public one?

I think the two go hand in hand. Memorialising allows us to mark the stark and brutal truth of acts committed – unambiguously. Remembering in its most private form allows us to see the complexity of truth, and to seek our own understanding of something that might otherwise seem fixed and definitive.

One can’t replace the other. Historians may estimate the number of lives lost, yet within that seemingly mind-boggling number are intimate losses – a father, a sister. And each single loss is immeasurable. Most readers have not lived through genocide, but many have experienced the death of a loved one. That can be a window into something larger.

To take that image of refraction that you mention, I suppose a memorial in the typical sense is imposing and opaque, whereas I hope my writing acts more like a prism that encapsulates the minute and personal while intimating myriad other lives touched.

Specifically, with time, your first novel has become part of the cultural record of Cambodia’s history. Has seeing it absorbed into that collective memory altered your sense of ‘ownership’ over it?

When I was an aspiring writer, I didn’t have such a book from my own people to turn to. Before I wrote Banyan, I used to feel that the Khmer Rouge experience was one I lived through alone, again and again – that no one could possibly understand what I’d survived.

My experience as a survivor is still uniquely mine, in all its specificity. So, to be honest, it still surprises me to hear another Cambodian say ‘That’s just what happened to me!’

While Banyan has been translated into 20 languages, for many Cambodians it remains inaccessible. For that reason, some of the most gratifying responses I’ve received are from other Cambodians, particularly the younger generations who have inherited the trauma. It’s important to me that the novel speaks not only to those far removed from Cambodia’s history but also to those who live directly in its shadow.

There are other resonances I could never have anticipated. From Iraq to Argentina, Turkey to South Africa, Brazil to the Philippines, readers have described to me how the work speaks to them on a very personal level. These are people seemingly without prior interest in Cambodian history. They write of the loss of family members, the loss of home, the fear of political persecution or upheaval, the destructive power of unchallenged ideology. In a world where the language of political violence is resurgent, where mass atrocities unfold before our eyes in real time, I hope that the story of one girl’s journey will continue to spur reflection about the consequences of our collective choices.

What freedoms – and what responsibilities – does fiction offer when writing about real histories of violence and displacement?

Fiction offers a safe place to view an experience from multiple angles. You can slip into the minds and hearts of however many characters you bring into the story. You can see through their eyes. That’s not only a freedom, though. For me, an author writing about real suffering, it’s a huge responsibility. In this sense, fiction is not magic conjuring up the improbable. It’s a mirror that reflects reality.

In both Banyan and Music, storytelling is used as a means of survival for the characters within. What do you think is the difference between telling a story to survive the moment, and telling it years later to survive the memory? Why is storytelling so critical in times of violence?

In the moment, when it’s a matter of survival, you tell yourself a story. You create a world to set yourself apart from the impossibility of that nightmare. Afterwards, it is a way of confronting what you have survived and why. It is a reckoning.

Both are acts of hope.

When I write, it’s with the belief that I am not alone, that there are others out there who might want to know my story, who might enter into it with me. I write not out of desperation but out of a sense of urgency, a feeling that this needs to be told and heard. It has become my purpose – even a reason for living.

In Banyan, the voice is that of a child shaped by your own lived experience; in Music, the narrator is more removed from your personal biography. How has your relationship to the ‘self’ in your narratives evolved between these books? What made you interested in writing your second novel with more distance – both in structure and subject – from your own experiences?

Both novels are deeply personal to me. It’s true that Banyan is more autobiographical. There is this child self that I carry within me. I needed to protect that self – who in the novel is Raami – and be faithful to her experience. While Music is not as autobiographical, Suteera draws on much of my own emotional journey. She’s an adult, her feelings and views much more mature and nuanced, so I didn’t feel I needed to protect her in the same way.

Banyan is a story that puts the reader in the act of witnessing. I was very conscious that, to fully grasp the horrors committed, the reader needs to confront the genocide from the perspective of a small child, and to hear her voice.

In Music, the atrocity is already established within the first pages, and the narrative is set in the aftermath. Probing the complexity of how this arose, and probing the relationship of perpetrator and victim, requires some distance – years of reflection. The novel is much more contemplative. The two principal characters, Suteera and the Old Musician, are worlds apart in their perspectives but bound by an interwoven past. I wanted the reader to be equally drawn to both. That called for a different approach to the writing, one that forces the reader to inhabit these dual realities, to feel the colliding force of their memories.

In both Music and Banyan, music and myth shape the narrative as much as memory or history. How do these different elements function differently in the act of storytelling? How do these non-verbal or non-linear forms allow you to tell truths that might resist more straightforward narration?

Truth itself is not linear – certainly it’s not straightforward. It’s multidimensional. The same truth can appear differently from distinct perspectives. If your intention goes beyond recording dates and events, you need a medium as multifaceted as the truth you’re trying to convey. Fiction needs flexibility, and the fiction that most compels me is acrobatic.

But I wouldn’t say that I chose music or myth to achieve a certain narrative effect. I listen to my characters, and these are just such essential aspects of their emotional worlds.

Within a piece of music, a memory is invoked, an emotion preserved. You think you’ve moved on, then you hear a melody, and everything comes back. For the Old Musician, music is at times the only way to communicate; words have become foreign, even dangerous. Music can also bypass memory. A song can assuage a pain whose origin you can no longer identify, a hurt that remains lodged in your body long after the memory that invoked it has receded.

As for myth, it is a collective creation. I think of memory as finite. It’s personal. Once you’re gone, that memory goes with you. Myth, by contrast, lives beyond you. It allows you to leap across time and geography. It’s shared memory that takes the shape of a tale, told and retold. My own story resides first in my memory, but my daughter can retell it in her voice, and others can pick it up and retell in theirs. And possibly it lives on indefinitely.

Your novels contain as much absence as they do detail: moments withheld, histories only hinted at. What is the value of acknowledging the limits of knowing, especially when writing about trauma? How do you decide what a story should leave unsaid, and what work those silences might do for the reader?

The most devastating thing for me is this: knowledge doesn’t bring back what is lost. You can know the past intimately, but that understanding doesn’t undo the destruction, doesn’t recover the lives buried in those mass graves. A daughter can stare at that monument of skulls, but even if she locates one that belongs to her father it doesn’t undo his death or his suffering.

Knowing is a kind of pain, and you must be certain that you can bear that pain before you go seeking answers. Sometimes the best way to drive home that sense of something between loss and death – that place of not knowing – is to make it feel that it’s just on the periphery of the pages. To describe it would lessen its magnitude and alter its emotional resonance. Little is said between Suteera and the Old Musician, but that does not indicate that they have little to say. Had they intended to voice it all, they would not have found the strength to face each other. In experiences of trauma, often the things unsaid bear the greatest weight.

I’m conscious as well that Music is a more demanding novel, in the way it asks the reader to grapple with this unknowing. It is perhaps easier to mourn loss and to feel the release of survival. But Music dwells on questions that are not so easily resolved, if indeed they are resolvable. Many readers have become accustomed to a quick pace of action and dialogue, and a clear resolution. The clash that happens in Music, by contrast, is of things remembered, fragments on the border of memory, the silence that surrounds the sound.

It’s been more than a decade since In the Shadow of the Banyan was published, and eight years since Music of the Ghosts. In that time, what in your relationship to these books – and to your writerly self – has changed the most?

Lately, I’ve been feeling that these two books are my other selves. I don’t have this struggle any more between fearing that these memories will be lost versus living with them daily, confronting each other in the battlefield of my mind. I don’t have to carry these experiences in my own body all the time. They have another place to go. When an emotion returns, I can tell myself, ‘Oh, yes, I wrote about that.’ That has brought a lot of comfort. The books are these other selves that understand an important part of me because they too embody what I’ve lived through. They now share the burden of remembering and preserving.

There’s a certain comfort in knowing that these stories now live with others as well. I’m also grateful to the translators who’ve devoted their attention and skill to my work. I can only imagine that a translator writing in Japanese, German, Polish, Russian or Czech is influenced by the language of war and revolution in their own societies, and I’m curious how that shapes their telling.

Interview by Samantha Ho.

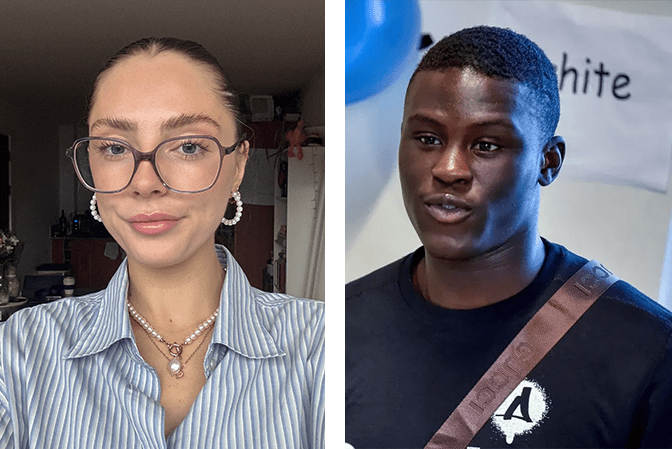

Vaddey Ratner, a survivor of the Khmer Rouge genocide and war refugee, is a Cambodian American novelist. She is the author of two critically acclaimed novels. Her debut autobiographical New York Times bestseller, In the Shadow of the Banyan, was a finalist for both the 2013 PEN/Hemingway Award and the 2013 Indies Choice Book of the Year and was selected for the National Endowment for the Arts Big Read program 2015-2016. Her second novel, Music of the Ghosts, was a New York Times Book Review Editor’s Choice and longlisted for the Aspen Words Literary Prize 2018. Her works have been translated into twenty languages.

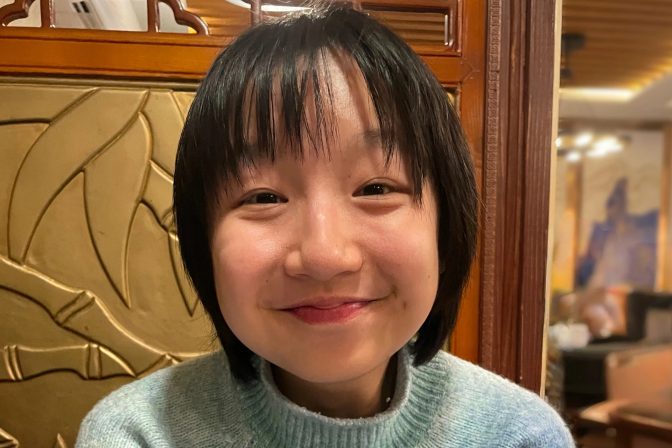

Samantha Ho was a Campaigns Intern at English PEN in June 2025 through the Laidlaw Undergraduate Research & Leadership Programme. She grew up in Los Angeles, and is currently a student at Brown University studying English Literature and Art History. Prior to her summer placement with PEN, Samantha spent the past several years advocating for global education initiatives.

Photo credit: Kristina Sherk