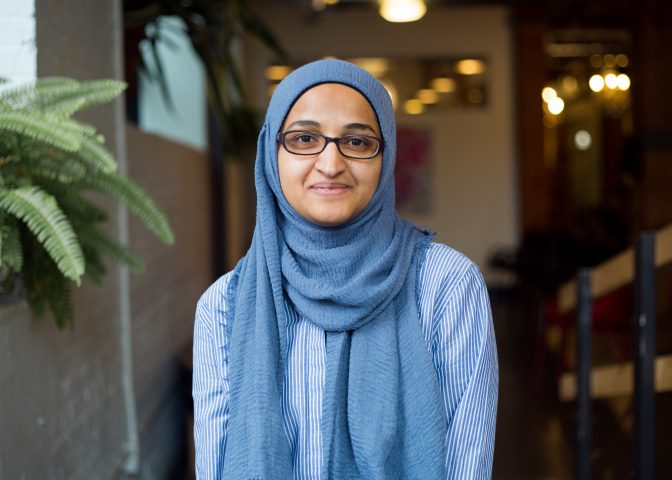

Hajera Khaja on telling her friend’s story.

PEN Transmissions is English PEN’s magazine for international and translated voices. PEN’s members are the backbone of our work, helping us to support international literature, campaign for writers at risk, and advocate for the freedom to write and read. If you are able, please consider becoming an English PEN member and joining our community of over 1,000 readers and writers. Join now.

This piece is in partnership with PEN Canada.

~

There’s a story I’ve been trying to tell for years. It is a story that is not mine to tell. It is my friend’s story and only she has the right to tell it. Still, I grapple with the urge to write it from my vantage point. I have written countless iterations before, each one taking me further, helping me to articulate what it is that I want to say, and why I want to say it. This is not my story. But within the story of my friend becoming a widow, there is my story too. About who I was and who I became, a before and an after.

My version begins several years before the inciting incident, when we met in university. We were in a meeting and the facilitator asked us to introduce ourselves by sharing one unique thing about us. I don’t remember what I said about myself. ‘I love to read’ was how I used to introduce myself back then. I kept it safe and predictable, the wallflower that I was, still am. My friend raised her arm high and spread her fingers apart. ‘I can do this,’ she said, bending the third phalanx of each finger while keeping the rest of her hand and fingers straight. I had looked down at my own hands and tried to replicate what she was doing, but I couldn’t. My fingers could only bend in the normal way. We became friends easily. We discovered that we both loved to write and commented devotedly on each other’s blog posts. We passed notes to each other in MSA meetings. We took painting classes together.

Most summers, my friend would travel to Egypt with her family. While she was away, I would write emo lyrics on her Facebook wall, quoting Macy Gray: ‘My world crumbles when you are not here.’ Another year, after reading Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, I wrote her a poem titled ‘There Is an Asmaa-shaped Hole in the Universe.’ That hole grew wider when she came back from holiday one year and revealed that she had met someone. She returned to Egypt that winter to get married.

I called my friend on the day of her wedding. Her sister snapped a picture of her while she was talking to me. That image of her in her pearl-white wedding dress, sitting on a garden chair, her joy palpable, even in that grainy image, is one of my favourites. A year later, she returned to Canada with her husband, her belly swollen. I visited her in the hospital the day their daughter was born. Her husband greeted us in the lobby, his face exploding with joy.

The following summer, the current Egyptian president overthrew the democratically elected government, and protests in response to the coup were met with gunfire. My friend, her husband, and their daughter had gone back for a visit. Before they left, before there was a hint of the impending violence, they were considering staying in Egypt for good. I met my friend and her daughter before their trip at a coffee shop called Yellow Cup Café. Yellow ceramic mugs hung from hooks above the food counter. Even the walls were painted yellow. When her husband came to pick them up, I told him, ‘Bring her back, please.’ Perhaps I should have said, ‘Please come back, both of you.’

The Rabaa Massacre happens. I spend all eight hours at work that day scrolling through news websites and articles, scouring Facebook for pictures and videos. ‘The bloodiest massacre of protestors in modern history,’ the headlines proclaim. I remember leaving work, walking to the subway station with a feeling of impending doom. I couldn’t fathom how people were going about their day, as if nothing had happened, while I couldn’t unsee the dead bodies lined up next to each other in a mosque, enormous blocks of ice on their chests, faces caked with dry blood; couldn’t unhear the gun shots, the sound of grenades bursting, the screams of women ringing through the air.

On 16 August 2013, I went to jummah. That morning, I had received an email from my friend, a reply to my message pleading with her to come back, saying that Egypt was becoming too dangerous, especially for her husband, who had a beard of the kind that made him a target. ‘Can Amr shave his beard?’ I had written to my friend, ‘So he doesn’t stand out?’ Her reply was not reassuring. ‘He went to the protests today, but it’s a very large one so hopefully it won’t be targeted by the police.’ About the beard, she said, ‘I asked him, and he won’t. And I respect that. Insha’Allah the protest is peaceful and nothing happens.’

I waited in the mosque for my husband after praying. He had left his bag and phone with me, so I scrolled through his Facebook feed – my phone was old and clunky and didn’t have any social media apps. I paused to read a post from an Imam in the UK, someone who knew my friend. His words felt like a whack to my throat. He must have mistaken her for someone else, I told myself. It can’t be her. I fumbled through my husband’s bag and took out his tablet. I tried to log into my Facebook account, but my fingers were shaking and wouldn’t land on the right letters.

‘Are you okay? Your face is pale.’ I heard my husband’s voice near me somewhere.

‘Asmaa. I need to check something. Her husband.’ My voice came out in a hoarse whisper. My husband took the tablet from me and typed in my password. I scrolled hurriedly through my feed, and for a sliver of a moment I felt relief. Nothing indicated that anything had happened.

And then that moment was gone. I saw a post from my friend’s sister: ‘My sister is a widow. Inna lillahi wa inna ilaihi rajioon.’ I don’t remember anything from that moment except my hand flying to my mouth, trying to contain a sob. It erupted anyway, pushed itself out through the gaps between my fingers, burst out from the corners of my mouth.

~

I called my friend that evening. I don’t recall who answered the phone at her in-laws’ home, or how I introduced myself. Such details have been lost from my memory.

“Assalaamu alaikum?” My friend answered, her voice weary.

I immediately felt guilt. She didn’t want to hear from me. I had called too soon. I was treading callously on her pain.

“Wa alaikum assalaam. It’s me, Hajera.”

“Hajera. Hajera.”

No one snapped a picture of my friend that day while she was talking to me. But I know now that images aren’t the strongest reminder of memory. Voices are, the way a name is stretched and elongated, as if it were something to hold on to, but falling just out of reach.

My best friend’s husband was shot and killed at a protest in Egypt, two years after they got married. My friend became a widow and her nine-month-old daughter an orphan. I don’t have the right to tell this story because it isn’t mine. But can there be another story here, nestled quietly within a larger one? Or maybe a story that’s entirely different, fighting for its own space, its right to exist. Like a series of concentric circles fighting to stay whole, resisting collapse into a black hole. I have been wrestling with these questions over the years.

After my friend returned to Canada, I didn’t know how else to be a friend other than to do what friends do: be there. I took the subway all the way to her parent’s house, where she was staying, and spent the day with her and her daughter. We would go for walks in the neighbourhood, bundled in our winter coats. We made lunch together – sometimes elaborate meals like salmon steaks and rice, other times simple ones like cream cheese and cucumber sandwiches. I read books to her daughter. She laughed as I said her favourite lines repeatedly, hoping that the sound of laughter could once again become familiar to us. I kept showing up at my friend’s house. I didn’t know if my presence was helping, but I knew the alternative of not seeing her was unfathomable; the last words I had said to her husband wouldn’t stop echoing in my mind.

Years later, a mutual friend suggested in passing that none of us were truly there for our friend after her husband was killed. Something unfamiliar unleashed from my body. I knew this person was projecting, that it had nothing to do with me or my relationship with my friend, but I couldn’t contain the anger in my chest. My worst fears had risen to the surface – that everything I did was worth nothing. That I failed my best friend. The feeling revisits me now. Am I failing her again by writing this story?

I am now forty, and have known my friend for more than two decades. She is still one of my closest friends. The story of what happened to her belongs to her, I know that. What I also know is that without her presence in my life, without the story of what happened to her, there is a different me. I don’t want to claim my friend’s story. But I don’t know who I would be if I hadn’t encountered such a heavy grief at that time in my life. If I didn’t teach myself to sit with its silence, to stay in its uncertainty.

~

This feels like a safe and predictable way in which to end this essay. It allows me to remain a wallflower, to claim that this is my friend’s story and to centre her, even as I talk about myself and my experience of her tragedy. But there is something gnawing at me that keeps getting harder to ignore. My writing this essay defies my claim of being a wallflower. It puts me at the centre, and being the centre of attention has always made me want to crawl out of my skin and disappear. Which then begs the question of why I’ve felt so compelled to tell this story.

The truth is that my friend’s story is my story too because it changed both our lives. Before self-publishing her memoir, my friend asked me if I could read it and give her some feedback. She mentioned me in the acknowledgments, thanking me for the inspiration for the idea for the book in the first place. She went on to publish two picture books, and to establish a publishing company that is now in its tenth year. What began as a writer-friend sharing thoughts transformed into me becoming an editor. If I work backwards, I wouldn’t be an editor and a creative writing teacher today if my friend hadn’t established her publishing company, and it wouldn’t be a stretch to sit with the question of whether my friend would have started her publishing company if her husband hadn’t been killed.

Who am I hiding from? I ask myself. Writers do this all the time though, don’t they? Take from what inspires them, build stories out of it. I have done this in my fiction too. But I have only taken from my own experiences, heavily changing any recognisable events and character details. The handful of times that I have written nonfiction, the stories have always been mine, a transformative healing announcing the end of the essay.

There is no healing in writing this. Only discomfort. Still, I will show it to my friend before it gets published. I know she will not object to any of its contents. She will tell me that it is very much my story to tell. We will shed tears over WhatsApp messages, reminiscing about the past, how little we knew about ourselves, how young we were. But I will still be uncomfortable. I will still cringe when I see this piece published. My fingers will tremble before I hit post on Instagram where I announce that I have a new publication.

And yet, I am choosing to write this, and agreeing to have it published. Maybe because even after trying for all these years to escape the reach of this story, it still comes back to haunt me. It’s the one essay that is sitting in my nonfiction folder, waiting to see the light of day. Maybe because, when all is said and done, we cannot escape the fact that the lives of our friends are also intertwined with ours. That a friend losing a loved one isn’t like losing a loved one myself, but it is like losing something. It’s losing the friendship you had built and not knowing how things will look moving forwards, how things will irrevocably change. I remember how hesitant I was in the days after my friend returned to Canada. I would email her instead of texting. I would say things like ‘Please don’t feel like you have to reply.’ I felt like an intruder. I’ve been seeing more commentary lately about the grief of losing friends, and how no one talks about what it feels like when friendships end. I felt it back then – the fear of losing my friend to her grief; the fear that my presence would just be a reminder of her old life.

Maybe I keep coming back to this story because I need myself to know something. That I did a hard thing by standing by my friend, offering whatever support I could. That her grief is a part of our friendship and inseparable from who I am now. Is that worth writing about? Is it worth the possibility that I will encounter readers who think less of me as a writer for writing a story that isn’t mine? I don’t know. No matter how many times I circle back to the question of why I’m writing this essay, the answer gets more muddled, and new questions arise, until all of it collapses into itself, and the black hole implodes.

Hajera Khaja is a writer of South Asian descent from Canada. She is an editor at an independent publishing company, Ruqaya’s Bookshelf, and runs an online creative writing program for Muslim women. Hajera’s writing has been published in various literary magazines and she was a finalist for the 2024 RBC PEN Canada New Voices Award. She has completed a short story collection and is seeking publication opportunities for it. She is currently working on various picture book manuscripts, a memoir about her writing journey, and a speculative novel.

Photo credit: Soko Negash