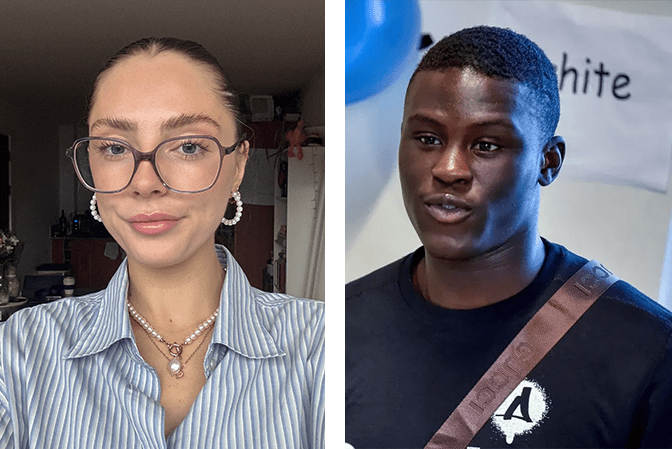

Jordan Aitcheson-Labarr on viewing a turbulent world through Hip Hop

PEN Transmissions is English PEN’s magazine for international and translated voices. PEN’s members are the backbone of our work, helping us to support international literature, campaign for writers at risk, and advocate for the freedom to write and read. If you are able, please consider becoming an English PEN member and joining our community of over 1,000 readers and writers. Join now.

What is the utility of art in a world in the throes of destruction? Every day we bear witness to people across the globe made homeless by climate catastrophe, families and homes brutalised by bombs, the greed of billionaire oligarchs and tech CEOs tipping countries across the world into fascism. As multiple crises compound one another, I have found myself renegotiating what I think about art and its usefulness. It’s been hard to imagine that things will get better before they get worse. And little by little the avenues of my liberatory imagination have begun to dwindle, and art has begun to look more like a refuge for distraction or posturing.

It feels like we’re entering an epoch of apocalypses, but so few of us have the energy left to do anything about it. How do you combat engineered moral apathy on such a scale? From which wells can we draw to ignite our collective creative energies? How can we hope to weather what comes?

I don’t know, nor do I think the answer is simple. But as the days and weeks lap into one another, a constant that has helped dispel some of my hopelessness and remind me of art as something other than escape has been Hip-Hop. What we know today as Hip-hop was birthed from a creolised synthesis of different diasporic cultures mixing in the heart of the Bronx, conceived as an expressive tool to give voice to the creativity, love, and anger of the residents of one of New York’s most impoverished boroughs. Hip-hop emerged from the harshest of conditions to consecrate itself as a precious platform for stories of love and histories of rebellion.

Genres analogous to Hip-hop have always been present in my life, with Reggae, Dub, Jazz, and Soul featuring as background music to memories of weekends cleaning the house or family dinners around the table. I see my love for Hip-Hop as a natural evolution from the habitus that was being built around me. The first Hip-hop album I remember hearing was College Dropout by Kanye West in 2005. My older brothers were able to sneak the CD away from my Dad when he wasn’t looking, and in our bedrooms we’d huddle around a busted CD player and listen to a young man from Chicago wax lyrical about his troubled life and hunger for ambition. I didn’t quite understand what I was hearing at the time, yet there I was, a 5-year-old walking around the house rapping “I’ve been working this grave-shift And I ain’t made shit/ I wish I could buy me a spaceship and fly”. What I knew at the time about the perils of retail labour and low wages was next to nil, but there was something both fantastical and familiar about the worlds contained within those records. It was only when I got older that I began to fully grasp the financial struggles that coloured my early years, making me feel things at the time that I couldn’t explain. Perhaps that’s why I felt an affinity to the music; it was offering words and insights to help me better situate my own experience in histories and systems so much bigger than me.

From Blues to Gospel to Negro Spirituals, Hip-Hop follows in a long line of Black musical traditions which oppressed peoples have used to envision alterities and fantasise better futures. The throughline between the music I grew up with and the music of my parents is that it was always more than artistic expression, it was a portal into a Black interiority that contained love, misery, and plans for escape and salvation. Hip-Hop is just one of the newer sonic iterations of what Black people across the diaspora have done since surviving their abduction from Africa and the harrowing middle passage.

Although the Kanye of today is a gross and tragic shell of his former self, I think the essence of Hip-Hop can most aptly be captured in that one bar of his in Gorgeous:‘Is Hip-Hop just a euphemism for a new religion? / The soul music of the slaves that the youth was missing.’ For me, there is something integral in this short verse – in how it connects Hip-Hop’s ties to the past and illustrates the link between the music of people who were grappling with their own apocalypses – and the music of today. It would be remiss to ignore the context of chattel slavery that made the sonics of enslaved people so urgent and complex; there are, of course, stark differences between the liberties we find ourselves afforded in relation to those before us. But the world in which we find ourselves comes with its own challenges. So when faced with forces seemingly beyond our control, looking back to when a group of people suffered an apocalyptic event can provide perspective to look at the tools they used to help them survive. The music of our past – and by extension art – has been used to communicate and contain powerful messages, evoking ideas of hope, while also having hidden messages codified in them to aid in escape and community building. Those same mechanics were not lost in time but trickled down and manifested themselves in the melodies and rhymes of some of my favourite MCs. From Mos Def’s ‘Umi Says’ to Noname’s ‘Rainforest’, to Denzel Curry’s ‘Walkin’ – Hip-Hop’s more radical essence has somewhat endured.

Yet, as is the case with many other counter cultural forms, over time, it has become subsumed in a capitalist model of production that has championed consumerism over struggle, making hyper-visible braggadocio and machismo in some of the genre’s biggest stars of today (think Drake pushing 40 and still rapping about how many women he’s slept with and how much money he has). Despite this, the genre is still very diverse and is more than the sum of its parts, with artists still managing to retain some essence of what made the genre so impactful to me as a child. Some of my first pieces of writing were 16 bars I’d try to frantically write out to rap over random type beats on YouTube, or to have freestyle battles with my brothers and cousins and friends. It was the first form of poetry that made sense to me, when all other forms I encountered in the Western cannon made me see myself in the third person, through the eyes of some European writer I was told I had to respect. Beyond seeing the value of Hip-Hop as an artform born from strife, I don’t have to listen to a song delivering some grandiose political treatise for me to consider it radical. Sometimes the most radical thing you can do is arm someone with a framework to regulate and understand themselves when they feel like everything else around them doesn’t make sense. For me, the Hip-Hop album that would do that was Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly.

I was 15 when I first heard To Pimp a Butterfly and had been following Kendrick’s journey since Section 80 and good kid, m.A.A.d city, but nothing could have prepared me for the beautiful chaos this album delivered. The album wears its influences on it sleeve, with elements of Jazz and Funk all over the album, colliding to illustrate the joy, pain, and contradictions endemic in Black America (and across the diaspora). The album is aspirational in what it attempts to strive towards, namely a reclamation of the humanity Kendrick feels has been stripped away from him and other Black Americans having grown up under carceral logics that negate their self-confidence and modes of expression. The album endeavours to be a wake-up call to love yourself despite the ways the world has hurt you. It was no surprise to me then that when the uprisings of 2020 began, and the air was electrified by a chorus of shouts demanding the deconstruction of systems of oppression, songs like Kendrick Lamar’s Alright were playing at protests.

Alright encapsulates the undulating hope one must have to imagine a world beyond the pain you might be experiencing. The track’s opening lines (also an interpolation of a speech from Alice Walker’s The Colour Purple) demand your attention by focussing on the mortal danger of life under the intersecting systems of racism and poverty, and how these systems make marginalised people combatants in games we never asked to play. As the song continues, it reaches its hook and culminates in the refrain ‘We go’n be alright’. It’s these few lines that you could hear often repeated at different protests, from the time of the songs release up until the uprisings of 2020 and today. The song borrows from the repetitive nature integral in the spirituals of the past in how its mantra-like chants engage audiences in a rhythm you can hold onto that matches your movement as you march along with it. I think songs like ‘Alright’ functionally and thematically hit that same resonance as the music from which they descend: they uplift and inspire us to resist the overbearing assaults on our daily lives and liberties.

Kendrick commented on the song in an interview with NPR some years ago, “Four hundred years ago, as slaves, we prayed and sung joyful songs to keep our heads level-headed with what was going on… Four hundred years later, we still need that music to heal. And I think that Alright is definitely one of those records that makes you feel good no matter what the times are.” While Hip-Hop can encode in its lyrics a belief that things can change, and that there is something better waiting for you beyond the hell you might be experiencing, it can also offer glimpses into much bleaker realities. Realities that assert that our world is beyond saving, that the damage is done, that – to borrow from one of Public Enemy’s lyrics – ‘Armageddon, it been in effect.’

I was 17 when I first heard Kendrick’s next album, and the world was emerging into a different place for me. I was entering my last few years of secondary school and beginning to question what it was I wanted to do with my life. I was lost and perhaps yearning for that same ecstatic feeling I was used to getting when a new Kendrick album came out. So, I pressed play, and then my optimism fell apart.

In DAMN, Kendrick takes a decidedly darker approach, with his machinations taking on dystopic tones. The world reflected in it is steeped in pain, a world Kendrick feels is out of control and out of sync with the hopes and dreams he once had. There doesn’t seem to be a way he believes we can remain like this. There is no tomorrow. These thematic threads appear in songs like FEAR,where he recounts instances of living closely with death, doubt and fear, opening the song with a monotone mantra that sluggishly spills his woes.

Why God, why God do I gotta suffer? Pain in my heart carry burdens full of struggle Why God, why God do I gotta bleed? Every stone thrown at you restin’ at my feet Why God, why God do I gotta suffer? Earth is no more, won’t you burn this muh’fucka?

It’s easy to see where his cynicism may have sprouted from. In the year before this album’s release, Black Lives Matter, as a movement and protest, gained significant traction in the wake of the brutal executions of two black men, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, by police officers in Louisiana and Minnesota. In conjunction with his growing rise to rap stardom and fans’ expectations of his political responsibility and other personal demons, DAMN culminates in a striking repudiation that the world as we know it can’t be saved.

It’s hard to salvage belief in a world you have become acquainted with through violence, and even harder to think it can be saved. Some Hip-Hop artists recognise this and continue a tradition of earthly rejection used by their ancestors, with folk music and Negro Spirituals possessing thematic similarities in how they can dismiss our material world in search of something else. Those who have abandoned notions of the world’s salvation are not inherently negative or naïve but seek to reemerge from the social relations that bind them into something new.

It’s been eight years since DAMN came out, yet we still find ourselves surrounded by images of death and state violence – continually enduring small daily traumas and sometimes feeling like it will not get better. Death by a thousand cuts. As artists and creatives living in an age in which we are encouraged to dismiss critical analysis as wasteful and see art as pure entertainment and escape, tracing the threads of Hip-Hop, from the past to the present, has helped me to continue seeing art as a weapon capable of arming you with a means to communicate and inspire. Hip-hop has reminded me that this latest iteration of terror only follows in a long line of others that our ancestors have fought in many forms.

In a video on the rap artist MAVI, writer Tosin Balogun discussed hip-hop and its place in times of crisis:

Hip-Hop itself will not save me or you. But I believe art in times of crisis to be the connective tissue that binds us and helps us understand ourselves. I still wake up every day not knowing the exact right way to help things get better. Or I feel disheartened, like I’m not doing enough. The answers to my fears are mine to wrestle with, but the important thing is that I surround myself with things that inspire me to keep going. It is not the song that’s important, but the feeling it’s left me with. It is what I choose to do after I take the headphones off. The apocalypse is here, but it has been with us for some time now, and what lies beyond capitalism is a mystery to me. But what I know for certain is that I don’t want to be dispossessed of my ability to try and imagine something different.

Jordan Aitcheson-Labarr is a creative writer from South East London and enjoys working across a range of styles, from scriptwriting to lyrical prose. His work has been featured by Theatre Peckham, Make It in Brixton, and the queer Black collective PRIM.BLACK. He is a graduate in English and Creative Writing.

Photo credit: Jordan Aitcheson-Labarr