AJ Layla on legacy and creative instinct.

PEN Transmissions is English PEN’s magazine for international and translated voices. PEN’s members are the backbone of our work, helping us to support international literature, campaign for writers at risk, and advocate for the freedom to write and read. If you are able, please consider becoming an English PEN member and joining our community of over 1,000 readers and writers. Join now.

This piece is part of a year-long series, supported by the Norman Trust, showcasing Gen Z writers and writing. Read our editorial on the series here.

~

Beth Pickens made her way to me through my computer screen on an end-of-summer afternoon – the kind where the sun is becoming italicised in the sky and you notice that the days are getting shorter again. I was attending a weekly series of writing workshops run by Sophie Robinson, and this week’s was about death and writing.

Pickens, an art advisor based in the USA, talked about how she helped artists through periods of creative block that often stemmed from fears common to all writers, one of which is death.

I was always acutely aware that I avoided setting pen to paper when it came to big ideas. Some sort of deep insecurity about the possible outcomes of my art becoming real. I say ‘acutely’, because, as we often do, I put a firmly sealed lid on these fears, never to be heard from again.

We were given a list of seven common fears surrounding death and asked to note down which resonated with us the most. I jotted them down on a notebook page whose margins brimmed with hand-drawn flowers and semi-realistic eyes:

1. I’m afraid to die because all my ambitions, my plans, my projects would come to an end. 2. I’m afraid to die because I would no longer be able to have any experiences.

I’m afraid to die because I would no longer be able to have any experiences.

Yikes. Not something I wanted to continue thinking about. Thanks, Beth, but I’d rather continue to procrastinate starting or finishing any of my projects. The lid went back on.

~

A year and half later, I’d quit my job and started an MA in directing. Work had made me stagnant; I barely had the energy to write, arriving home from two-hour commutes on cramped, narrow trains and falling asleep almost immediately. This was going to be my opportunity to spark that inner creative electricity again, taking those previous writing projects a step further by turning them into films.

My months studying culminated in a film about my family history, exploring themes of migration and identity. As a writer, I’m used to working solo on creative projects. In film, the process is entirely different.

Initially, I was bubbling with ideas. My Pinterest board and notebooks swarmed with images: Narcissister’s colourful and cluttered sculpture of her dead mother’s belongings, David Syke Tatler’s bright and playfully accessorised sock puppets, Edith Di Monda’s cool and mysterious house hats. Trying to bring my ideas to life, I got to work on making a replica of Young & Marten, an old hardware store that used to stand in Stratford. Primary colour paints, cardboard, and some string. My partner would sit at my desk, trying to concentrate on her big nine-to-five responsibilities, whilst I would keep interrupting from the floor to ask if she thought the cardboard building fit well around my face.

Once I began painting, the fun began to disappear. Splendid yellows and grumpy blues gradually turned my prop into a block of cartoon cheese. What had been a solid and coherent idea in my mind turned into something confused, unsure of itself. I didn’t have any time to fix it.

To my surprise, showcasing the pre-vis went fairly well. The audience giggled at my blue and white polka-dot sock puppet; its brown wool hair crazy like mine. They responded well to the stories told by my parents about their childhoods and where we’d all come from. It should have filled me with confidence and pride, but I couldn’t shake off the feeling that something was off. The bubbling ideas were boiling over the brim and dissipating.

~

When I was 15, my nanny passed away from cancer. She’d had it twice before, once before I was born and once when I was 14. The third time it was terminal. My father remembers her as a strong woman who had endured hardship, not only surviving it but living on to become what I remember of her. Encouraging me to have as much sugar as possible at breakfast time; playing cards with her and her friends, gambling in gummy packets; wearing the ponchos, hats and scarves she knitted for me in the biting English winters.

I’m now down to only one living grandparent; both of my mums’ parents had died before I was born. The three losses began to feel more significant as I grew older: I’d lost the opportunity to find out more about my great and great-great grandparents, about these particular paths of my ancestry. My grandmother was from Chakwal and my grandfather was from Amritsar. We don’t know how they met, what their lives were like before they came to England, or the choices made by our ancestors that led to the existences of my cousins and I, all born and raised in London.

1. I’m afraid to create because all my ambitions, my plans, and my projects will come to an end when I die. 2. I’m afraid to create because I will no longer be able to have any experiences when I die. 3. I’m afraid to create because everything before me that has died lives in me now, and I must do it justice.

The lid had come off, the stifling anxiety overboiling. Spilled, it was undeniable. I had to do something to lift this fear of death and legacy.

~

In a weeks’ time, I would be visiting my remaining grandparent in the mountains of Galicia, so I decided to take off with my camera and work out the rest once there.

For the first few days, I ran around frantically, camera at my hip, trying to find a way to shift my fear. I searched in the tops of trees, among marsh green leaves changing into terracotta red. I searched in knee-deep bushes growing smaller strawberries and rounder plums than you get in supermarkets back home. I focused my ears, trying to discern the sound of strolling breezes from lolling sea foam in the distance. In the end, I gave in.

‘I’ve got a migraine,’ I told abuelo. He abandoned planting avocado seeds and sent me to my room with old packets of paracetamol. I climbed into bed, the room unnaturally dark for an early afternoon in the summer. My fingers reached out to the bedside table, reflexively searching. They only found a glass of water.

After the migraine had subsided, I texted my partner about how I was feeling. I’d been trying to film constantly since I’d arrived, hoping each day that something would click and the whole film would be done, just as I had envisioned on the plane over. Her response came: ‘I hate that what started out as a project you were really passionate about and loved has become tainted by others’ opinions.’

This, so simple in its care, was kaleidoscopic. I could see, between the haunting shapes and lurid colours, that I was devastated to face the truth of what had ruined this film for me: I was so worried about doing my imaginary ancestors proud, and creating something my imaginary offspring could connect with, something I had never had, that I was struggling to ground my project in the present; I was only ever looking to the looming deaths of my past and future, and the thoughts of people who did not exist in this exact life, in this exact moment.

The next morning, I used everything in my power to stay present, to follow my gut. I found joy and humour and playfulness in my piece that I’d failed to see – or understand – before. In the editing process, I worked hard at experimenting with my resources, again staying present in my choices, following these instincts with which I was becoming more in tune. I found pride and determination and satisfaction. My artist’s gut is still in its infancy. I still find myself fearing death, and the pressure of artistic legacy. Pickens, in Make Your Art No Matter What, talks about creating a death acceptance practice in which you find small ways to accept death every day. By following my instincts, I am staying only in the present, accepting and co-existing with the presence of death of the future and the past. In doing so, I find life and creativity and success.

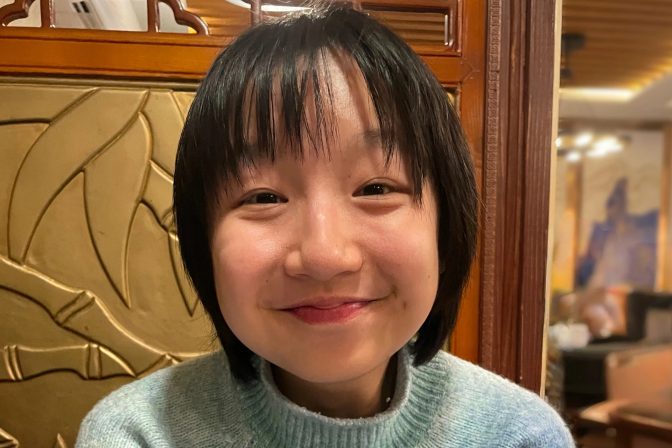

AJ Layla is an emerging filmmaker and writer from East London who has a strong focus on themes of transformation and overcoming. During their BA in English Literature and Creative Writing, they became a published writer in poetry anthologies and zines. Falling in love with scriptwriting, they went on to complete an MA in Directing for Screen and Stage, where they were involved in writing-directing various short films and stage plays. Recently graduated, AJ hopes to continue pursuing bold, creative, political art whether that be through the medium of film or writing.

Photo credit: Mariam Jallow