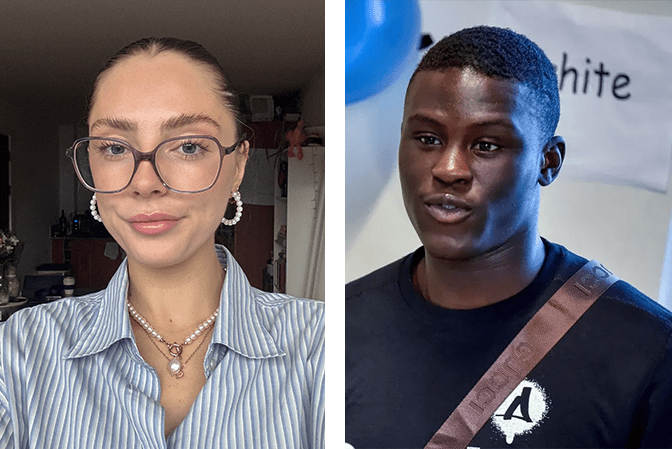

Adèle Oliver on drill, resistance, and the Art Not Evidence campaign.

PEN Transmissions is English PEN’s magazine for international and translated voices. PEN’s members are the backbone of our work, helping us to support international literature, campaign for writers at risk, and advocate for the freedom to write and read. If you are able, please consider becoming an English PEN member and joining our community of over 1,000 readers and writers. Join now.

Towards the end of 2020, on evenings where 5pm felt like midnight and midnight came with a thickness I could not wade through, I took to watching UK drill ‘type beat’ tutorials on YouTube. The gritty Brixton-born rap subgenre had already been written off as inner-city criminal fodder by the media–politician–police trifecta – a process that had happened a few years earlier, when the style was more obscure and was easily disfigured by broad-stroke dismissals (“nihilistic nonsense”, “knife crime music”, “gangland soundtracks”). By 2020, drill’s eminence could no longer be denied. It emerged – a slippery, indelible thing – from inky alcoves to the sterile light of the pop charts with the irreverence of a once-in-a-generation prima donna. As breakout drill artist and then Daily Mail favourite Headie One said that year, ‘I love the truth ‘cause it make them uncomfortable, my lifestyle’s wonderful.’ What a time to be alive!

I needed get closer to this thing. So I entered the genre’s engine room, the underbelly of its tsk-tsk-tsk clomp: the rolling hi-hats that popped like my cracking joints, the snare drums that ranged from slap-in-the-race to punch-in-the-gut, the ghostly melody lines that snaked around the elixir on the poet’s tongue. That is to say, I watched producers – usually teenagers swivelling on gaming chairs in brightly lit bedrooms, dragging oblongs into mosaics of chord sequences and drum patterns, and clacking against noisy keyboards that reminded me of GP surgeries – construct the zany soundscape of a generation. The end product was a ‘type beat’: a high-quality instrumental with all the hallmarks of [insert your favourite artist or producer’s] sound. This was usually posted to a separate video, accompanied by the BPM and essential information for bedroom recording artists.

Beneath these videos, among a sea of emojis, entreaties, eulogies (‘killed it bro 🔥 🔥🔥’, ‘too 🥶🥶🥶’, ‘can I hop on this one 🙏’), several comments beckoned ‘read more’. I would oblige, and read stanzas that were sometimes organised into full song structures and often written in languages didn’t understand: Serbian, Vietnamese, Tamazight, Hindi. I instinctively mumbled the lyrics I understood and liked the comments that forced my brows into furrowed approval and my lips into a taut smile. If you closed your eyes, you could hear the mimicked rapper slide over the familiar textures. If you strained you could hear their voice becoming your own, you could feel your rhymes taking on the vim of a superstar’s. Every night I got to crack open creative expression, peering into its arrivals, departures, returns. It was addictive.

Falling down these behind-the-curtain rabbit holes isn’t unusual; I have spent countless formative hours on trawling through YouTube, ripping over-compressed files from pirate websites, priming myself for my yet-unrealised appearance on a BBC4 music documentary. But, on a particular evening, it took on a new hue. I was on a postcolonial studies master’s programme, and each week we looked at a different form of regional anti-colonial resistance. We called each of these forms ‘postcolonial objects’. This week’s object happened be created by Rap Against Dictatorship (RAD), a Thai collective who used their music to resist the country’s military junta, emboldened by ongoing structures of ‘crypto’ colonialism.

The guest lecturer played a clip of one of RAD’s songs. The connection was choppy, so notes skipped and jutted out of place. A flutter of recognition forced me out of strained daze: I knew the music’s next move, the ghostly, reversed synth pad that crackled out of my laptop speakers, the haunting ebb and flow of the chords followed my humming like a shadow. It was one of the type beats I’d listened to. I was almost certain it was created by DefBeats, a prolific teenage producer who, unlike some of my other faves, rarely did tutorials and never showed his face, just churning out hundreds of beats on his page instead. Everyone else on the call seemed, as far as I could tell, unmoved by the song. But I felt the thrill of puzzle pieces snapping together like these bedroom producers snapped quantised notes onto their digitised staves.

The song, ‘Reform’, became a soundtrack to pro-democracy protests across the country. The YouTube video for it, which currently has over 10 million views, could not be accessed in Thailand after a government blockade. This transnational crossover made me think about how indispensable drill is, how necessary. This rap group in Thailand, formed under the pressure cooker of its military government, bought a type beat from a kid in the UK and used it to mobilise on-the-ground resistance.

On the first anniversary of Art Not Evidence, I’m reminded of this story, and of the parts of drill, obscured by racist moral panic and grandstanding about its lyrics, which first pulled me down the rabbit hole in which I still roam. Drill’s lyrics and the poetics are, of course, art in and of themselves. They should be protected. But let’s not forget that, when drill is criminalised, the foundations of this sonic force, the defiance it demands, and expression itself are under threat too.

We believe that art, and particularly rap music, should be protected as a fundamental form of freedom of expression, and should not be used to unfairly implicate individuals in criminal charges. – Art Not Evidence Mission Statement

This is what I remember when I write an expert witness report, when the creative musings of a child, enthralled by the same sonic rebellion that captured me, are twisted into evidence of gang affiliation and inherent criminality; and when, four years after my late-night type beat rendezvous, I’m in an alternative provision school in Birmingham, surrounded by a dozen very excited 16 year olds. We’ve transformed the deputy head’s office into a driller’s sanctum: mic connected, lights dimmed, hype men ready. I had to bribe them to sit through an hour-long workshop on the criminalisation of drill with the promise of this studio session. Almost all these children, who for a host of reasons were not in mainstream schooling, from the aspiring rappers who had bars stowed away in notes apps to the quiet ones who denied any affinity to music in the workshop, took to YouTube to find the perfect type beat to record over. I watched them burst from confines of narratives placed on them into the warm embrace of sliding 808s and booming kick drums.

‘Put OFB type beat.’

‘Nah, actually this Peezy one’s hard.’

‘Coldddd.’

‘Miss, can you download this?’

And so, I diligently ripped their requests from YouTube, fragments of lyrics flitting from too-bright screens to my ears, then my lips, tugging the corners of my mouth into a knowing grin. Just like old times.

Adèle Oliver is a writer, artist and PhD researcher from Birmingham. Her book Deeping It: Colonialism, Culture and Criminalisation of UK Drill counters panic-fuelled discourse on UK drill, gang violence, and knife crime, ‘deeping’ drill as a complex Black artform, born out of generations of commentary on and resistance to technologies of colonialism, consumerism, anti-Blackness, and more. Adèle is also a core member of Art Not Evidence and works as an expert witness in cases that use Black youth culture, music, and idiomatic language as evidence of bad character, criminality and/or gang affiliation. Outside of this work, Adèle is a musician, producer, and avid capoeirista.