Lina Attalah’s PEN Pinter Prize 2024 speech.

PEN Transmissions is English PEN’s magazine for international and translated voices. PEN’s members are the backbone of our work, helping us to support international literature, campaign for writers at risk, and advocate for the freedom to write and read. If you are able, please consider becoming an English PEN member and joining our community of over 1,000 readers and writers. Join now.

This speech was delivered at the PEN Pinter Prize ceremony at the British Library on 10 October 2024.

~

I met Alaa for the first time at a protest calling for the independence of the judiciary in 2006. We were in our 20s. He was effervescently protesting with his whole body, jumping up and down like fire. Shortly after, he was pulled by several cops to a police truck. Judging from the scene, he seemed to be enacting a bodily resistance as he was dragged by the police. We always smile when we remember how our first physical encounter is one where his full presence is being actively negated by the police. We laugh at how unflattering the scene was for a first meeting.

Shortly after Alaa came out from his imprisonment, he had an idea. He wanted to convene an assemblage of inventive techies with a heightened sense of political consciousness. He was of the blogging generation and was on the forefront of it; but he was never content with sitting back to think on his own and perform to an invisible public from behind a computer screen. He wanted to go wider and deeper; wider by summoning a convention and deeper by interrogating the very techne through which a whole new politics of expression was emerging.

He wanted to test what it means to work with tech tools to open up channels of knowledge making, ideating and developing discourse. The quest was political, the façade technological, the approach philosophical. We convened techies from across the Arab World, who are also artists, organisers, writers and thinkers. It was our first encounter with how to think and organise intersectionally, with how to break categories open and smuggle their substance from one to the other; technology to politics, philosophy to technology, technology to art and journalism, and so on. You could say it was a kind of rehearsal for the Arab Spring, with our newborn community boasting members from Tunisia, Syria, Palestine, Bahrain and Lebanon among others.

When the Tunisian revolution erupted in December 2010, I was with Alaa in Pretoria, South Africa. He had then moved there to work with localisation software, a technology he was militant about; he wanted to see an Internet where Arabic content flowed seamlessly as though it was its native language; the Internet being, back then, a possible site for an embodied universality.

I cut my trip short to rush back home, get a visa and go to Tunisia – but the wave of Arab revolutions was moving faster than flights – and Egypt’s own revolution broke out on 25 January. I was beaten by the police, who broke my glasses. I wrote to Alaa that day about how he had missed an unflattering scene of me being beaten up and losing a shoe and, most importantly, my glasses – and my vision with them. But we agreed that something new was emerging in the blur.

A few days later, Alaa would pack and come back home; at the time, home was Tahrir Square. Days after, the president had fallen, the government had fallen, the parliament had fallen, the constitution had fallen. I met Alaa in Tahrir Square: he had a list on a draft paper that he was crossing out. Revolutionary change was a laundry list in Alaa’s hands. He was striking out items, and writing out new ones that now needed attention.

What comes next is yet another formidable presence, not confined to protest squares. Alaa went on working with different formations, students, activists, journalists, techies, artists. He taught workshops on how to write a political statement as a poetic act. He worked with youths on how to inhabit the formulaic informational space of Wikipedia with homegrown narratives. He led code sprints for localisation tools. He led meetings on how practicing politics online – as opposed to through the political party – had restored space for emotion.

Let’s Write Our Own Constitution – one of Alaa’s initiatives. He admired South Africa’s experience with the Freedom Charter, primarily for the process of assembling its content through the active instruction of the public to politicians. Rescuing democracy from its representational reductionism, he was dreaming of smuggling Kilptown’s democratic experiment to Egypt, where people, clustered in communities, would convene to write parts of a proposed new collective constitution. Its content inside, he had his eyes on how this form of convening, of coming together, would affect the outcome.

In the months to follow, there were many reversals to the revolutionary triumphalism that we experienced in the early days of 2011. But the ultimate reversal was in 2013: a military coup. By then, my newspaper’s management had decided to pull our funding – as an act of censorship. I became jobless alongside 25 journalists colleagues. I had an intuition that this was going to be the summer of unprecedented political violence and finitudes. I asked Alaa to help us build a website where we could house our displaced journalism, to at least bear witness to the coming summer of violence. He spent days and nights with his partner Manal back then, writing code for our new website. Meanwhile, I was diverting my anxiety about a starting our new project, a project that may stand in the face of the violent annihilation of our voices by playing with Khaled on Alaa and Manal’s couch, as both were busy writing code. Khaled, their son, was almost one by then; he was birthed in a moment of birthing, when the revolution was ascendant – and was now wrestling to make his way into so much uncertainty.

By the time our website, Mada, was up and running, the military was in power and Alaa was in prison. He finished developing our code in smuggled letters and instructions during prison visits. In the ten years that followed, there would be two active bodies of archives of the military’s violent cancelation of public politics: sustained publishing in Mada, and letters to and from Alaa.

Alaa’s handwriting in the letters is barely legible, and reading them is an exercise of deciphering. Sometimes I do it with a common friend, Sarah, who also sends and receives letters. The exercise reminds me of an eerie image described by Frantz Fanon from 1954 of Algerians trying to tune to the jammed transmission of the revolutionaries of Radio Free Algeria. We would start reading some of the letters together, it would turn into a spiritual ritual of some sort, where Alaa is summoned, and suddenly there is much more to the content we are reading. Such is the possibility of form that Alaa was always militant about.

Sometimes, the two archives of Mada and the letters would converge; Alaa’s first years of imprisonment were marked by a determination that a voice can transcend confinement and trespass. His body was incarcerated, but his voice was fugitive. With profound depth, the kind he is ordered to summon within a prison architecture, he wrote about failure as instruction, progress as ideology, Palestine as universal politics.

In his later years of imprisonment, Alaa’s writings shifted to his own predicament as a prisoner, again universalising it to urge a solidarity embodied in a belief that this concerns us all, that we too can be prisoners like him one day. Why? Because states ultimately survive through preserving their right to enact power on our bodies. In a text he wrote in 2019, he described with graphic precision a violent account of his incarceration. He did not do it to invite us to pity him, but to understand that the Authority’s enmity with its opponents is predicated on the negation of the voice and the body. This is a moment when the political failure of the collective has returned us to the body as an ultimate site of resistance.

In 2017 Alaa wrote, ‘I am in prison because the regime wants to make an example of us. So let us be an example but of our own choosing. Let us be an example, not a warning.’ Five years later, he went on his longest hunger strike to demand freedom, and escalated it to a water strike. He survives an imminent death in a moment he movingly describes in a letter. He is woken from unconsciousness to find himself in the arms of his cell mates, some looking at him with eyes terrified by yet another possible loss. Some held his head with care, others held his back. He put it in words and an image was born. Ordained to a jail cell with no exit in sight, Alaa restores his attachment to life through inmate solidarity, not just as his own particular condition, but as a reminder that unrestrained power is built on confinement. And that those in confinement must not to be bracketed off to a margin, a human rights category – they need to become the issue of all issues, the cause of all causes. And for this to happen, there needs to be solidarity.

Today, his mother, Laila Soueif, is on hunger strike for him. Today is Day 11, because 11 days ago, Alaa actually completed his latest prison sentence of five years, but still has not been released.

Sometime in the 1930s, Bertolt Brecht orated a speech to an anti-fascist gathering, in which he spoke about the courage of recognising the truth when it is hidden, the skill to turn it into something we can fight with, the cunning of finding in whose hands to put it and spread it. Through years of a friendship I am so privileged to have with Alaa, I witnessed his digging into origins like a philosopher, turning his findings into political artifacts for organising and mobilising like a politician, and then, essentially putting it all in our hands in codes, letters and articles like an orator.

Alaa’s is a friendship that unleashes political imagination He is a pedagogy that keeps giving, through words and silence. He is the ghost of spring past; he is the absentee we should all summon to presence.

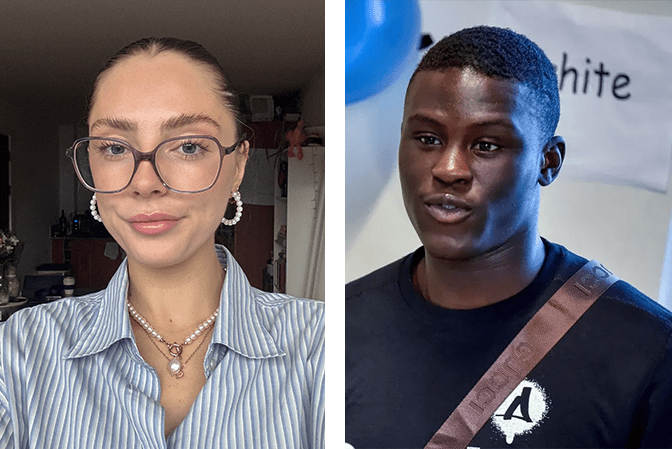

Lina Attalah is a journalist and founding editor of Mada Masr, a Cairo-based independent media platform, where Alaa Abd el-Fattah published many of his writings.

Photo credit: George Torode