Tayiba Sulaiman on memorialisation.

PEN Transmissions is English PEN’s magazine for international and translated voices. PEN’s members are the backbone of our work, helping us to support international literature, campaign for writers at risk, and advocate for the freedom to write and read. If you are able, please consider becoming an English PEN member and joining our community of over 1,000 readers and writers. Join now.

This piece is part of a year-long series, supported by the Norman Trust, showcasing Gen Z writers and writing. Read our editorial on the series here.

~

I’m wearing the wrong trousers for trespassing – summery and wide-legged, they keep snagging on bricks. It is August 2023, and I’m climbing over a half-collapsed wall of the former Ljubljanska Banka in Mostar, Bosnia. I’m yet to be convinced that going in is a good idea. More than this, I am worrying about whether it’s right. At the top, I turn around to lower myself down to the ground floor where my family are standing. Before I jump down, I catch sight of a woman on the balcony of the apartment behind the building. She doesn’t smile. I feel a chill go through me. The building is not supposed to be accessible to the public; the local council have boarded and fenced up all the entrances, except for this accidental opening around the back.

In theory, I celebrate civil disobedience, but in practice I’m already feeling there’s something fundamentally wrong about our being here at all – not just because of the rules of the present, but because of the burden of the past. This was once a space of militarised violence. Because of its height, the building was occupied by Croat forces and used as a sniper tower during the two sieges of Mostar, the first of which began in April 1992 and the second around a year later. The building’s grand glass façade was shattered, and has now been cleared away as if it never existed. Only concrete remains. Abandoned after the war, it has become a sort of unofficial gallery for street art, graffiti and murals. And it was this we wanted to see.

I’d worked with Remembering Srebrenica the year before I started university. It was likely because of a heavy awareness of human suffering during the Bosnian War that, when I had the chance to visit, I’d expected to find its legacy memorialised everywhere I went. Of course, the idea of memorialising a war is much hazier than I’d assumed it to be, especially where an agreed version of events is still being debated. At the Srebrenica memorial site, I read a 2021 report which describes the ‘opposition to the official recognition or condemnation of the genocide by states, local governments, and institutions’ in the region. The war is over, but the story isn’t.

The traces of conflict are impossible to miss – there are bullet holes in so many buildings in Sarajevo and Mostar, and many testaments to the dead. There’s the fountain in Sarajevo’s Veliki park paying tribute to children killed in the siege, the statue of Ramo Osmanović calling for his son Nermin, the endless white stone gravestones of those who were killed during the war. But I suppose what surprises me is how inconsistent the attempt to make sense of the war’s brutality seems. We’d visited Mostar’s Museum of War and Genocide the day before, and were bewildered to discover how blurrily the conflict’s historical context was presented. It felt like an avoidance of finger-pointing, of accusation. We had watched footage from November 1993 of the destruction of the old Stari Most, Mostar’s Ottoman bridge, as Croat Defence Council soldiers cheered, but later, standing with crowds at the reconstructed bridge, we struggled to track down an acknowledgement of what had happened there. (Online, I find a plaque in Croatian naming and condemning its destruction, but in English, there’s only a stone that reads ‘DON’T FORGET ‘93’, without contextual information.) During our trip, we visit several museums documenting the Bosnian genocide, none of which are state-funded. They are supported by the Dutch government, in atonement for the massacre that Dutch UN forces allowed to happen at Srebrenica. The British government also contributes financially towards the upkeep of these museums – even as it looks directly past the genocides it is endorsing elsewhere in the world. There is a process of memorialising, but it feels like it’s always slightly out of your line of sight.

It is clear to me that this tower can’t be treated like a tourist spot. I’d read several accounts of it where the fact that it was once used to murder people from a safe distance was almost ignored. I didn’t want to barge in somewhere demanding to see the art, disregarding the wishes of the people – perhaps even of the artists – and I didn’t want to stir up the ghosts of the crimes that had been committed there. It seemed to me that there was something sacrilegious about it.

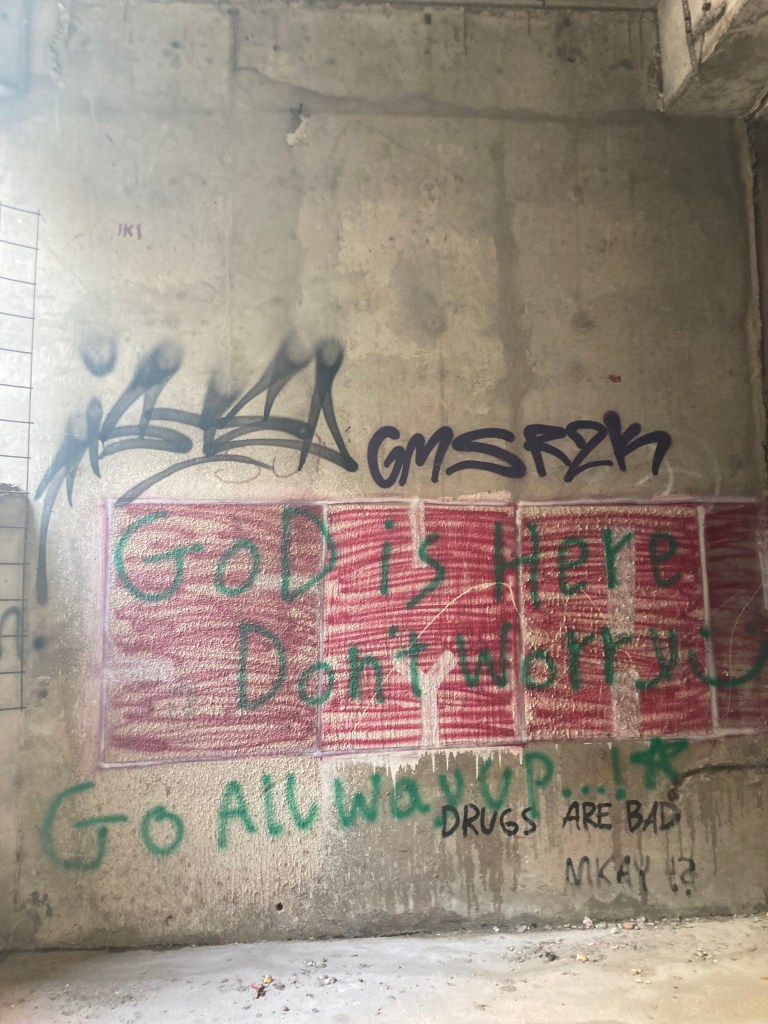

I stand there on the ground floor, trying to decide whether it would be better to turn back. Turning, I catch sight of my dad walking past a wall, on which someone has spray-painted the words:

God is Here Don’t Worry 🙂 Go All way up…!

I am thrown by the idea that someone has predicted exactly my sense of doubt, moved by the fact that they have somehow eased it. I hadn’t expected the building itself to coax me forwards. I hadn’t expected to find something holy here.

~

I trail after the others, who are already exploring the bottom floor. Standing water expands murals of warped, ghostly faces and makes mirror-images of the words. The first thing that stands out is how multilingual the graffiti is. Some German phrases are printed in block capitals – ‘DEIN TUN DU BIST’; WHAT YOU DO IS WHAT YOU ARE. Even the inscription FCK AFD. Later, I find whole excerpted paragraphs from Homer in English, alongside insults, questions and declarations. If the artists who have taken over this building have an argument to make, it’s not one that has been communally decided. These multilingual voices speak past each other, between each other, around each other.

Where one artist’s work has spread out to cover parts of an older contribution, these voices overlap. It’s a completely different model to the established avenues through which we usually find work in translation. Here, space is as in demand as in a packed magazine. Everyone is after the best spots. But, in this case, there’s no point at which the work is finished. It’s last come first served. For me, this building is a place where established ways of doing things – of making art, of translating, of thinking about the past – are jumbled, exposing their weaknesses, and where the whole question of the value of a consistent, coherent take is thrown into question. In a way, the building is like an anti-gallery. There’s no governing board to steer the direction of its contribution to Bosnian history or culture, and there are a fair share of names scratched into the stone. There’s no single curator, no strategy of inclusion or exclusion. Anything can – and very likely will – be overwritten by anyone.

Slowly, we begin to head upwards. I hadn’t expected the overwhelming openness. Forget bannisters, railings, or anything else to hold onto. These stairs don’t even have walls. It’s a risk assessor’s nightmare, but there’s something liberating about the false sense of dizziness induced by the sweeping skyline. It’s safe enough, so long as you’re sensible and avoid the edges. I feel like a child riding a bike without stabilisers. But I can’t get too comfortable, because even if there’s no danger now, the awareness of past threat hangs over me. So much of this art is haunting; the mural of shifting faces which spans a corner, warping outwards, and the sly, subtle warning to avoid the exposed lift shafts where someone has spraypainted two arrows, one pointing upwards and one downwards, respectively labelled ‘HEAVEN’ and ‘HELL’. The fall would be fatal. It’s a privilege, of course, to wander through this place in a time of relative safety. I find myself longing to know when exactly each piece of graffiti was done, to help put a context to this strange balance of beauty and of sinister reminders.

To my surprise – despite my feeling of solemnity – so much of the graffiti is out of pocket, even funny. On one wall on a higher floor, in front of a stunning view of a hill which holds the city in its palms, someone has spraypainted ‘RATE THIS PLACE ON TRIP ADVISOR’ and completed it with a line of stars. It makes me laugh at its daringness, its cheekiness, in English, making a demand of us, understanding us as interlopers. While the first bit of graffiti that had encouraged me onwards might have wanted people to visit, the sentiment isn’t necessarily shared by all: these artists won’t let us get too comfortable, and they know who we are. I love this sharpness and humour, which goes on in the face of its own destruction, its anarchic defiance. Here, the past isn’t something to be swept away or standardised or replaced with a nice, coherent, comforting argument about the human capacity to kill or the grand horror of war. In the tower, ruin is met with something utterly and undeniably alive.

From the highest floor, we look down and see my mother and my youngest brother below us in the park, playing on the bridges over the water. Snipers once took aim from the top of this building, and here I am, waving at the tiny forms of the people I love most in the world. Maybe it’s the greenness of the water, or the beautiful mosques and churches tucked behind every street corner, but Mostar feels like a peaceful place today. From this vantage point, I wonder how much of that peace is the sort that survives on silence, or at least relative quietude. The worst traces of the war have been cleared out of sight, but the bruises remain, and if you stray too far from the centre, you find places like this, where the legacy of the war still throws a long shadow. I find many things in this strange tower on the city’s edge, but peace and quiet isn’t one of them. It feels busy, loud with all the voices it contains. It echoes with the laughter and disagreement of artists, teenagers, soldiers and ghosts.

~

The sniper tower stands tall as a reminder that whether we assemble memorials to a nation’s history or demolish all traces of war and conflict, we are constantly curating a relationship with the past. A messier, more multivalent way of engaging with shared history will continue somewhere out of sight. If we want to see this in action, we must seek it out and make sense of it for ourselves. I suspect that this is really where my initial discomfort was rooted. Entering a space like this can feel like taking the burden of understanding, of a fair and nuanced approach to atrocities, entirely onto your own shoulders. There’s no approved version of events explained neatly on the walls; you might not be armed with a reading list; there’s no state-sanctioned approach that will tell you what to think. I’m not sure that this passive but comfortable engagement with the past on predetermined grounds is the most responsible way to look at history as it stares up at you from beneath the rubble.

I maintain that there’s great value in staying sensitive, to remaining somewhat in awe of a place and its ghosts. But I also think we need to interrogate the feeling that things would be better if someone else could just think their way through the problem of reading the past for us. Sometimes you need to jump the fence and see for yourself. I had worried about disturbing a grave silence here that doesn’t exist the way I had imagined it. Instead, the tower is an open-ended place of countless voices speaking past and to one another, and I’m glad I took the chance to hear them. From the top of that building, a place where the past is so visceral and unsettled, the present looks different to me: equally unmade, equally full of overlaps and disagreement, and yet constantly in danger of being shaped into stories that tell us, comfortingly, that they are complete.

~

We leave the building; it’s getting late. We stop to play in the park, where we pick ripe figs, climb over the fountains, and take photos of my little brother in front of the incongruous but delightful statue of Bruce Lee. A bridal party drives past as we walk over a roundabout and towards the city centre, honking their horns loudly. The ease of slipping back into every day life here makes me even more aware of the quiet with which a place’s history can recede from memory, conveniently pushed to the parameters again.

Where will this impulse to forget, whether it comes from the people or the state, leave places like the sniper tower? Perhaps it’ll be boarded up again for another decade; perhaps it’ll be demolished; perhaps one day, the history will be put to one side, and it’ll be renovated into upmarket flats, like Berlin Prenzlauer Berg’s Wasserturm, which contained an early concentration camp in 1933. The tower stays in my mind as I first saw it, with my little brother playing in the concrete skeleton of what was once a glass revolving door. All that’s left is a cylindrical structure jutting out onto the street corner: four panels of concrete and four gaps. On three of the panels, a pale blue starry night is painted, with the same phrase written underneath in English, German and a third language. Google Translate tells us it is Bosnian, but an alternative, perhaps more accurate name is BCMS: Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian. All of these are one language, divided up to fit today’s national borders. I picture my little brother weaving between them, unaware of what this place has meant and may go on to mean. And I imagine myself, doubtful and curious, standing under its odd canopy, reading the same words in each language: WE ARE ALL LIVING UNDER THE SAME SKY.

Tayiba Sulaiman is a writer and translator from Manchester. She graduated with a degree in English and Modern Languages in 2023, and completed an Emerging Translators Mentorship with Jamie Lee Searle in 2024. Her recent translations from German include poetry by Swiss-Croatian writer Dragica Rajčić Holzner and a verse script for the 2024 Droste Festival at the Centre for Literature, Burg Hülshoff. She also writes poetry and prose; her work has appeared in Prospect Magazine, Briefly Write and on The Poetry Business’ blog. She is a member of The Writing Squad.

Headshot credit: Rumaisa Jilani

Photo credits: Tayiba Sulaiman