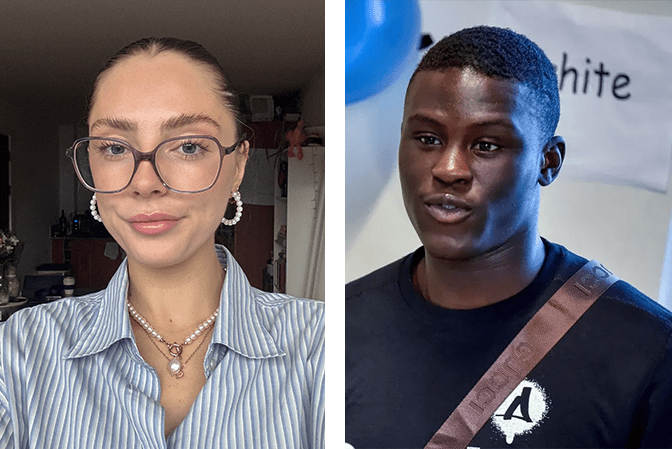

Abhijeet Singh on the relationship between photography and literature.

PEN Transmissions is English PEN’s magazine for international and translated voices. PEN’s members are the backbone of our work, helping us to support international literature, campaign for writers at risk, and advocate for the freedom to write and read. If you are able, please consider becoming an English PEN member and joining our community of over 1,000 readers and writers. Join now.

This piece is part of a year-long series, supported by the Norman Trust, showcasing Gen Z writers and writing. Read our editorial on the series here.

~

Photography is literature caught in the act. I know Tarantino, for one, would like that sentence. A postcard, a passport-sized picture of your lover, an album from childhood revisited for humour and nostalgia. Newspaper cutting, GQ cover, even a souvenir snapshot for home when you’re in Paris. A photograph is to visualise a book when looking at a tree. It is a genre-breaker. The most remembered pictures are those without form. However, more often than not, pictures demand a ‘toast’. A call-to-gathering of its viewers, in the form of words. A line or two. Stating the obvious; painting the obvious. A quick handwritten note by the photographer on the side of a picture. A circa, a name, a city. Or a printed side inscription on a postcard. ‘Tomb of Amīr Khusrau’. Accentuated. Red ink. Maybe the initials of the Witness. Back-of-the-book style. Or a caption, as we call it on Facebook or Instagram. A line or two, implying a succinct, light-hearted voice. Playing it cool. Keeping it simple. Or a long caption. A poem. Prose. Minor essay. Minor visual note. Whatever. Putting up a picture evokes a companion in the form of words. This could mean many things to many different people in many different situations. However, what runs through the idea of describing or narrativising photographs is more than merely a mental note. As Roethke once said, ‘When is description mere? Never.’ Especially in times such as ours, we cannot afford to trivialise the language that accompanies the image. We can barely trivialise the trivial anymore. A photograph, taken today, demands to be reiterated in words. As opposed to a toast, one might say that a photograph is asking for a eulogy. That it is a death of a moment. Similar thoughts were expressed in On Photography by the legendary Susan Sontag. She said that ‘a camera is a sublimation of the gun, to photograph someone is a subliminal murder – a soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time’. There’s no denying the fact that we’re in a sad, frightened time. But I wonder what the Palestinian genocide would have been had we never seen it. It is precisely the opposite of what Sontag then says about the camera. The process of capturing a moment is always going to be hounded by the question of ethics and intrusion. Photography, like literature, is a matter of subjective standpoint, and it is only through a note of context provided by the sources that produce it that one should assume the merit of a picture. A photograph, in this sense, feels like a conjoined twin of language itself. A photograph can be deconstructed into three essential entities: a visual or an image; an Eye (presence of a vision); and an observation. Language can be dissected similarly, and it is interesting to see the counterpart of the photographic trinity: an implication; the Inner Eye (presence of a sensibility); and a confrontation. The innate desire to bring these entities together and pair them with their respective counterparts is what makes modern photography a crucial part of civilisation. We desire to take a picture and turn it into a document. This is more intricate than can be said. After all, when is a description mere? It might be a random coincidence that writers have shared great admiration for photography. (No generalisation intended.) But from what I’ve seen in my experience and from my interest in the lives of my favourite authors – Akhil Katyal, Asad Ziadi, Tishani Doshi – most of them like the idea of capturing the moment. It is joy. Not singular, but multitudes spread in the vast sea of memory and its insistence on preservation. We see poems, but we also see friends, cows on the way to work, road signs, trees, weddings and sneak peeks into the parties where writers meet and hold talks. A caption of a picture of a road sign. A reference to the Indian government hellbent on rebranding places with colonial or Muslim names to ‘Hindu’ names, a train that aligns with their hypernationalist, divisive politics. Suddenly, the act of taking a picture becomes a responsible action. Especially in countries where one can go to jail for it in the name of demeaning the government. In such cases, language plays a pivotal role. It is through words that you navigate you opinion both inwards and outwards. And then: post on Facebook accompanied by prose of conversational style. Embedded with personal narratives, inside jokes, and literary allusions. Rare pictures of poets hanging out together in the corridors of a college. At a house gathering. And then: pictures of life and excerpts of articles. Writings that are socially insightful and politically aware, capable of bringing attention on their own, but which when accompanied with photographs of the mundane shine through the unspeakable film of reality. Philip Larkin and Allen Ginsberg were big-time photographers too. Books of photographs published, driven by the want to have a world frozen in time. A memory suspended in the air. Lasting forever in reminiscence. Ginsberg’s photographs were accompanied by his handwritten captions. From writers to philosophers to theorists, debates around photography have been inconclusive. Ironically, no matter what you write about a picture, it leaves space for more. Today, Palestine has all our attention. Pictures we see coming from Gaza are meta-dystopic. A photograph of a child with eyes open, severed limbs, and his mother crying next to him. 150,000 likes on Instagram. People fighting for and against in the comments section. It becomes necessary for us to ask whether a photograph can stand for itself in the kind of world in which we live. Is it so that a genocide shown through pictures is outsmarted by the genocide explained in the caption written for the pictures? How then does the language complement the medium of photography? No matter how inhumane the subject of the image, people are apathetic. The other extreme is bewilderment. Writing about Susan Sontag’s reactionary views on photography, Judith Butler says, ‘As much as she disdained those who are always shocked anew by the atrocities of war (what does one think war is?), she is surely equally alarmed by coldness in the face of such image’. It’s mind-blowing to think that they wrote this almost two decades ago, a stark reminder of the little progress we’ve made. I wish I were a pessimist, but this is the truth. Plain and simple. We are either making faces in an attempt to be sympathetic or we are simply indifferent to these photographs. Butler further writes in the same thread: ‘Her [Sontag’s] complaint is that it arouses our moral sentiments at the same time that it confirms our political paralysis’. This is the point of a mental block for a contemporary poet like me. I come from a third-world country and I’m writing this from a comfy, soundproof library in a first-world country. How is my language enabling the dead? Or what is my role as a witness? The viral Joseph Fasano poem ‘Rumi’ made its rounds on Twitter and Instagram asking us the same. To witness the graves. The irony is that we see the human corpses in these pictures of genocide, we read the posts with grief and outrage, and the absurd nature of the algorithm demands us to ‘like’ them. You double-tap the image, like a heartbeat. A heart-shaped hollow fills up with the colour red. The more hollow likes, the more popular it gets. Recently the ‘All Eyes on Rafah’ template was the most popular, ‘trending’ image on the internet. Such is the nature of language in 2024. We are reduced to statistics, both in terms of creativity and mortality. In the confines of such linguistical structures, dominated by power and romanticism, one finds the disquiet of an untitled/ uncaptioned photograph rather appealing. Every sentence in this framework starts acting like a rogue citizen. Like a superpower adamant on destruction and apocalypse. It’s a dreamy thing to say in pop culture: ‘I wish the films were true’. Now, they finally are. Time and again, we find ourselves caught up in a matrix. Pushing through our fetish for simplicity and capitalist, alternate selves. Like Scorsese’s Paul Hackett in After Hours. Or Ray’s Arindam Mukherjee in The Hero. Strangely, I find myself giving examples of – and thinking of – straight, heterosexual men. As a queer person, the energy I feel surrounded by and engulfed with is masochistic, rowdy, savage. Trust me, this is involuntarily so. All of a sudden, the world has turned into a caricature of Bukowski, the drunk, wife-beating, bankrupt male. All other identities are howling from the margins to no help. Again, it’s a metafiction. It’s all the voices echoing all at once in the same void. I don’t care to be politically right. India, the country I come from, is on the verge of turning into an absolute dictatorship. Political correctness is the last thing that should be asked of us. Students and their teachers are being attacked, left, right and centre. I’m 23 and I know everyone around me is depressed and looking for ways to escape this bleak reality. I shouldn’t be writing this, ideally. Palestine shouldn’t have been bombed. No content-writer should gear up to write tearjerker articles for readers who are tired and bored of repetition and sensationalism. The likes of Plestia Alaqad or Motaz Azaiza don’t deserve to photograph their fellow citizens being bombed to powder. It is humiliating to read a note below a picture of a headless, dead infant saying ‘The Beheading of Children in Gaza’. No amount of philosophy or literary theory can compensate for the kind of information with which we are triggered. I rephrase my opening sentence: photography today is dystopian literature caught in the act, and captions are the laughter of those who are making it happen. This stimulation, sandwiching us between ideological gratification and emotional quicksand, is no better than drug abuse or communal lynching. It’s horrifying that, despite so many established knowledge systems about psychology, philosophy, mental health and their intersections, nobody talks enough about our language being infiltrated with two extreme attitudes: indifference and pretence. We always choose one of them. We don’t know better. As a postscript to this article, the readers are naturally forced/ conditioned/ programmed/ subjected/ devised to continue serving the norm. But the fabric of language is so. It deceives, and in the process of deception reveals itself. Like a photograph, the case of language is inconclusive too. If a photograph needs a caption to help with the question of selective contextuality, what does the caption require to beat brain-rot? There seems to be no light at the end of the tunnel. The animators have not stopped drawing the tunnel itself. It’s just a long cyclical journey through language to a better understanding of it. What we turn towards is a photograph; what we make of it is a caption.

Abhijeet Singh is a multilingual poet, translator, essayist and playwright based in Manchester, where he is currently a student of Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University.

Photo credit: Abhijeet Singh