Ma Thida on freedom, art, and Myanmar.

PEN Transmissions is English PEN’s magazine for international and translated voices. PEN’s members are the backbone of our work, helping us to support international literature, campaign for writers at risk, and advocate for the freedom to write and read. If you are able, please consider becoming an English PEN member and joining our community of over 1,000 readers and writers. Join now.

Freedom is generally seen as the fundamental right of each person to act, speak and think without hindrance or compulsion. People need freedom to chase their dreams and voice their convictions. We normally believe that to nurture and enable the growth of imagination and innovation, freedom is essential. But the reverse is true, too: freedom finds its fullest expression through creativity. This is why I say: creativity rests not just in the freedom we have, but also in hunting for freedom we want.

Before 20 August 2012, the environment for freedom in Myanmar was grim: enduring, extensive and prolonged censorship, alongside comprehensive state propaganda. Then, on that day, the pre-printing censorship process was suspended. But though the so-called freedom of the press was introduced, writers and the media could still not feel free; they remained tightly bound by their subconscious minds, shaped by decades-long state censorship, and the pen remained chained to the hand of censorious peers and the censorious self. Self-censorship was ingrained, and it took time to find an exit. And peer-censorship was even more sensitive – it was novel, stemming from new forms of group pressure, and would require new forms of resistance.

While ‘media freedom’ became a positive catchphrase among political activists who had lacked the opportunity or privilege to apply for publishing licences throughout the military era, there were other sides to it, too. Many military-backed media outlets were recklessly disseminating the horrific news from Rakhine state without adhering to journalistic ethics, fanning the flames of hatred ignited by racial and religious discrimination. Censorship – all the barriers to a free press – was an obstacle in addressing hate speech propaganda – something the PEN Charter sees as an ‘evil’ of the free press. I doubted the new ‘freedom’ we had in 2012.

~

In 2013, with the establishment of organisation registration laws, PEN Myanmar was formed. We employed creativity and engaged in numerous expressive projects to pursue the true freedom we desired. PEN Myanmar’s first project, the Conflict-Sensitive Media Monitoring Survey, aimed to uncover evidence of how media freedom had been exploited to fuel hatred and social discord, identifying both the perpetrators and the media platforms utilised for such purposes. Across 2014 and 2015, we undertook various projects – ‘peace writing contests’ for short stories and poetry, poetry slams, ‘literature for everyone’ (Yatha Asone Asan) initiatives, literary evenings – designed to fight the fight against hate speech, promote peace through creative expression, engage with minority language communities and, crucially, provide a platform for communities to exercise their right to free expression while nurturing an essential and vibrant literary culture.

One standout project was Literature for Everyone Creative Expression (LFECE). Literary talks have been popular throughout Myanmar’s history – albeit usually adopting a lecture-style approach. While some reading groups would hold discussion-based events, they were not accessible to the broader public. With civil liberties a fundamental principle for democracy, PEN Myanmar endeavoured to establish LFECE as an inclusive, aesthetically driven, secure platform.

Over the space of a decade, PEN Myanmar organised over 150 LFECE events, across fourteen states and divisions and in the Naypyidaw region. Participants from diverse backgrounds – students, farmers, labourers, office workers, religious practitioners, writers, literature enthusiasts from different ethnic groups – joined these activities. But as that decade passed, regulations were imposed on such literary talks, due to the perception that they often veered into political discourse – advocating for democracy, criticising the military, and scrutinising the government of the time. Obtaining permission to hold them became harder. Our LFECE events took place in small communal venues – monasteries, libraries and churches, with smaller groups of attendees. We had to be creative. But it meant we could engage with local writers, poets and – especially – youth who were aspiring to become authors.

The fundamental requirement for participation in this project was wholehearted engagement. Members of PEN Myanmar – renowned writers and those writing anonymous– would recite their works or sometimes works they admired, inviting the audience to respond either through commentary or by presenting their own pieces (regardless of whether they had been published). Occasionally, members would deliver poetry or visual performances, encouraging active participation from the audience. And in many instances the audience responses exceeded expectations. In one village, an illiterate farmer joyfully contributed impromptu poetry, likening her experience to the rising sun despite her age being akin to sunset. Her expression of freedom was applauded by the entire audience.

The true success of this endeavour lay in the community’s belief that, through LFECE, they had begun to recognise the role of creativity and literature in advancing and safeguarding freedom. They had gained the opportunity to share their creative expressions on an equal footing with well-known writers and poets, and had learned how to engage in respectful, mutually listening discussions on other political, economic and social issues. In many instances, community members were moved to tears, their voices genuinely heard and valued, a newfound freedom they had never before encountered.

~

PEN Myanmar’s leadership was able to establish relatively accessible channels of communication with the National League for Democracy (NLD) government. Consequently, we intensified our advocacy efforts, conducting initiatives such as a ‘Freedom of Expression Roadshow’ to fourteen regional parliaments, campaigning for the Right to Information Bill. We continued to focus on informative, analytical and creative endeavours, including Edu-entertainment programmes promoting federal democracy, conducting ‘literature inclusiveness surveys’, and facilitating capacity-building programmes that trained student union members to become champions of freedom of expression. We continued to organise numerous literature-related activities – LFECE, the Link the Wor(l)ds translation workshop, Collective Dream poetry performances, literary cafés, literature evenings, a short-story writing curriculum, screen-writing courses, and creative writing workshops featuring both international and local authors.

Many writers’ organisations in Myanmar prioritise purely literary endeavours, often misconstruing PEN Myanmar’s initiatives as reliant on foreign funding. But our primary objective has always been to safeguard and advance freedom of expression, fostering a vibrant literary culture and establishing a connection between formal education and literature. Despite criticism, we have merely employed creativity in our activities to pursue the freedom we aspire to achieve.

I steadfastly believe in the power of creativity as a means to broaden our freedoms, recognising freedom is not fully attainable only through practical means – especially in my country. The act of being creative doesn’t require permission from external entities, including censorship boards. But once our creative acts are published, our physical and social freedoms become endangered. Repressive regimes curtail our civil liberties, arbitrarily arresting us and imprisoning us as means to control and suppress dissent. And so when it comes to creativity, freedom is not simply a matter of chance. It is a result of a conscious choice.

~

After the coup in 2021, several writers met untimely deaths. Others endured arrest and imprisonment. Others found themselves without platforms to exhibit their work as the military revoked news outlets’ licenses. But, despite the upheaval, many writers remain in Myanmar, continuing to write without expecting publication, financial gain, recognition, applause; without fear. They have harnessed their creative freedom to explore diverse means for readers to interact with their creations.

Before the coup, many writers and poets actively contributed to online platforms, attracting sizeable audiences. But the surge in arbitrary arrests linked to social media posts has led to a reluctance – on 13 April 2023, Kyaw Min Swe, an editor and journalist, was apprehended by the military shortly after he changed his profile picture to a black image in solidarity with the victims of airstrikes on a village in Sagaing Region. Meanwhile, the doubling of data prices and the rising cost of SIM cards, combined with the decrease in writers’ incomes, has greatly restricted online accessibility. Nevertheless, over time new online magazines and YouTube channels (operating from foreign countries) have emerged and gained traction, notably supporting fundraising efforts for the Spring Revolution against the resurgence of military. From time to time, these channels also release audiobooks of well-known novels and short stories.

In March 2021, the military announced that issues falling under the purview of the News Media Law and the Printing and Publishing Law would be subject to adjudication in military courts. These courts possess the authority to impose capital punishment. Despite the prohibition of certain pro-revolution writers’ works in local bookstores, some publishing houses have managed to release novels and other literary works. While some writers still find it necessary to remain in hiding, book launches have become spaces where some can safely engage with the public.

~

The enactment of the Organisation Registration Law in October 2022 intensified requirements on associations like PEN Myanmar, with severe penalties for activities that diverge from the regulations. Now we require additional creativity to sustain our work, with our members dispersed across various locations. I cannot divulge the current activities of PEN Myanmar. What I can affirm is that we continue to employ our creativity in pursuit of the freedom we aspire to achieve.

Writing demands reflective time. For writers, creativity is not only about freedom but also about the pursuit of it. Censorship restricts the publication of literature, but not its essence of freedom. Tragically, in June 2023, Nyi Pu Lay, president of PEN Myanmar, passed away due to a medical emergency while in hiding. But we discovered that, in that time, he had penned numerous short stories under pseudonyms, and sketched landscapes from various parts of the world. He had used his artistic ingenuity to carve out the freedom he sought.

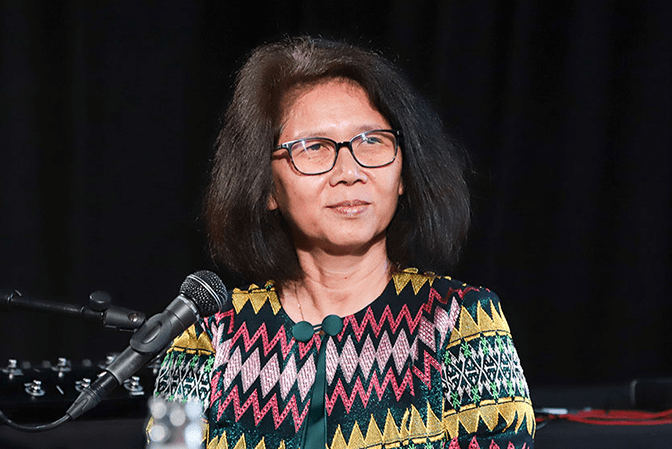

Ma Thida is a medical doctor, writer, human rights activist and former prisoner of conscience. In 1993, she was sentenced to 20 years in prison for practicing freedom of speech but was released in 1999. She was awarded international human rights awards, including the Reebok Human Rights Award, the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award, Freedom of Speech Award and Disturbing the Peace; Courageous Writer at Risk Award. She was the inaugural elected president of PEN Myanmar from 2013 till 2016. She served as a board member of PEN International from 2016, until she was elected as chair of their Writers in Prison Committee in 2021. She was a research associate at Southeast Asia Studies council at Yale University for 2021–2022. She moved to Germany as a fellow of Martin Roth Initiative for 2022–2023, and is currently a fellow of the Writers in Exile programme of PEN Germany.