Sophie Lau on the complex relationship with her mother tongue.

PEN Transmissions is English PEN’s magazine for international and translated voices. PEN’s members are the backbone of our work, helping us to support international literature, campaign for writers at risk, and advocate for the freedom to write and read. If you are able, please consider becoming an English PEN member and joining our community of over 1,000 readers and writers. Join now.

It is October and I am in Andong, South Korea, trying to find the meeting spot for my shuttle bus. I say ‘shuttle bus’ very loosely, here – all the regular ones have been cancelled because it’s the off-season, and the tourist centre had to call a private bus driver for me. I ask an ahjussi who’s passing by and he points me in the right direction – but not before expressing surprise at my travelling alone. ‘It’s dangerous for a young girl like you to travel alone,’ he says. ‘Where are your friends?’ I tell him they’re all in England; I’m met with more surprise. ‘Are you not Korean?’ I smile politely and shake my head, say that I diligently started learning Korean four years ago, and that I’ve put more effort in recently to make my solo trip just that bit easier.

It isn’t the first time that I’ve passed for either a local or a gyopo on my trip. And with each case of mistaken identity, my feelings become a little more complicated. Of course, I feel a certain pride in being able to communicate in a language I’ve taught myself – I had set a goal to learn the twenty most-spoken languages in the world after reading Gaston Dorren’s Babel – but there’s also a layer of guilt starting to settle in my stomach. Have I really devoted that much time to perfecting languages that aren’t my own?

My two weeks in South Korea follow three weeks in Hong Kong with my paternal family. There, as I tiptoed around what could and couldn’t be said given the political situation, there was an added sense of discomfort: all the gaps in my linguistic knowledge. I’d wanted to rediscover the island and had deliberately ventured into the small pockets of Hong Kong where barely any English was used. But though I could get by with my limited literacy in restaurants and cafés, when I visited my grandmother in her residential home for the first time, I realised I didn’t know how to write her name in Chinese for the visitor log. I couldn’t read the signs showing the names of each room’s occupants either. With each day, as I listened to my aunts and uncles conversing during yum cha, as I listened to the news playing on the TV in the background, I realised how limited even my spoken vocabulary was. I realised for the first time how much I had neglected Cantonese; how much distance had grown between me and my mother tongue.

Language loss is an unfortunate reality shared by many diasporic communities. But I cannot help but feel particularly frustrated that I am a professional linguist who isn’t fluent in my heritage languages. Being that I am also a writer, the irony of my being close to illiterate in Traditional Chinese is not lost on me. There are at least six other languages in which I’m more proficient than Cantonese. I often wish that weren’t the case. Sometimes I find myself contemplating how advanced my Cantonese would have become if I’d devoted my attention to it, rather than my other languages.

As my career progresses, and I receive more requests to work with heritage and community languages, my thoughts increasingly turn to language preservation. Although Cantonese is my mother tongue, I have never felt too worried about its extinction – there are currently over 80 million Cantonese speakers, and enough written records to ensure its legacy. Hakka, on the other hand – the language of my maternal family, an unwritten Chinese dialect – causes me a lot of language anxiety. While all my maternal aunts and uncles speak Hakka, I am the youngest member of my family that still knows it. Of the handful of my older cousins who grew up speaking it, none of them have passed it on to their children.

My maternal grandmother looked after me a lot when I was a child. She can only speak Hakka, and so I had to learn it too. All the other Hakka speakers in our family know either Cantonese or English as well; when my grandmother passes away, there will be no pressing need to continue speaking it. It will only be a matter of time before all traces of Hakka will vanish from our family, before Hakka culture becomes only a part of our history.

To live in the diaspora is to simultaneously preserve your heritage and embrace your culture. What I have realised, however, is that these two do not always easily coexist. Although my cultural identity is a blend of British and Chinese, my linguistic identity is far more imbalanced. Far less easy to categorise. My goal was to learn the world’s twenty most-spoken languages. But these days I have a different one, one that’s no less difficult: to find my way back to my heritage languages.

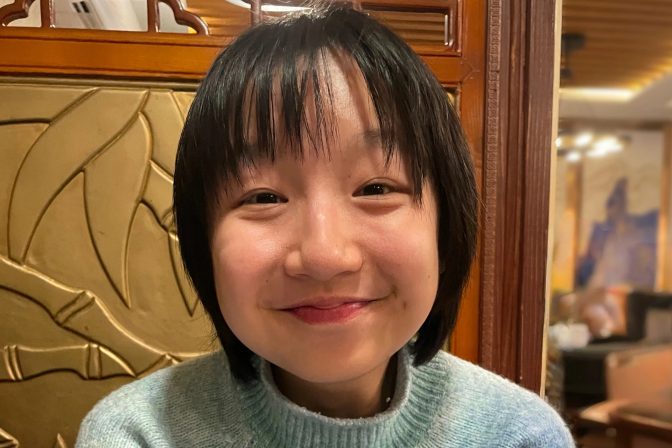

Sophie Lau is a freelance writer, educator, and generally vibing polyglot who can be found in the UK, Hong Kong, or almost anywhere else in between! Her writing includes multilingual poetry, personal essays, language listicles, and whatever else tickles her fancy, but her current labour of love is a fun-filled YA romcom! She also designs and delivers creative translation and writing workshops. In her free time, she enjoys learning languages (she’s currently battling with her tenth!); hanging out with her dogs, Doughnut and Tiny; and capturing her rather chaotic solo travels on film.

Photo credit: Sophie Lau